De Antonio was not only a supporter and distributor of other directors’ films, he was an active participant in the New York art world, a scene which he documented in his 1972 film, Painters Painting. During the 1950s and 1960s, he worked to connect artist friends with gallerists and collectors, calling himself a “catalyst” rather than an agent. As chairman of the Rockland Foundation, de Antonio set up a concert for avant-garde composer John Cage, a man he called, in an interview with Cage biographer Roy Close, “probably the most important person I met in my life.” When Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns were living in such poverty that they didn’t have proper facilities, they showered at de Antonio’s country house. De Antonio also helped Johns convince important gallery owner Leo Castelli to give Rauschenberg a show, a major coup that jumpstarted his career.

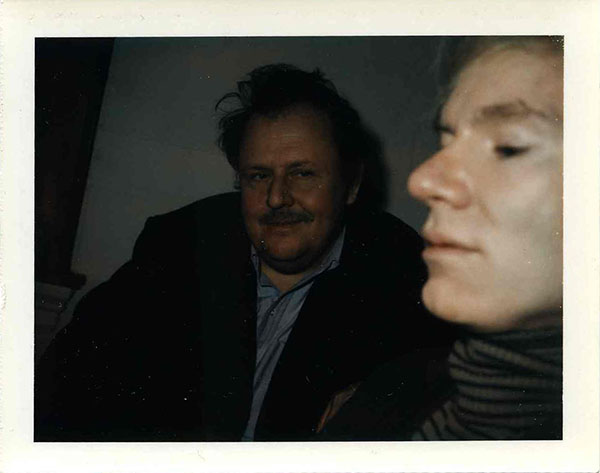

De Antonio’s most significant friendship, however, was with pop artist and filmmaker Andy Warhol. The two were long-time friends, and Warhol credited de Antonio with encouraging him to become a painter. Warhol wrote glowingly of de Antonio in his 1980 book Popism (co-authored with Pat Hackett), saying, “De was the first person I know of to see commercial art as real art and real art as commercial art, and he made the whole New York art world see it that way, too.” Not only that, Warhol made a seldom-seen film of de Antonio called Drunk, part of the series of early films that includes Sleep and Eat. As early as 1965, de Antonio tried to make a film about Warhol for Czech television. He partnered with writer Jiri Mucha on the proposed film about the Czech immigrant, who was born Andrej Warhola, but correspondence in the collection suggests that Cold War tensions prevented the collaboration. De Antonio remained interested in Warhol, and even taped an interview with him in 1981. Emile de Antonio and Andy Warhol

Emile de Antonio and Andy Warhol

“Like the McCarthy film but without McCarthy”

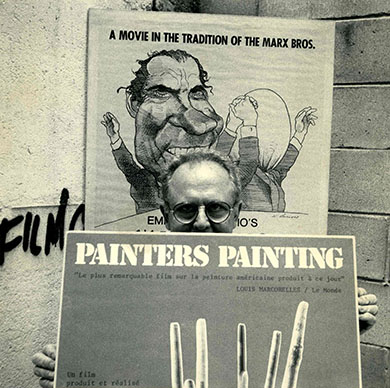

De Antonio completed Painters Painting in 1972, urged on by his wife and art critic Terry de Antonio (née Moore). De Antonio saw Henry Geldzahler’s 1969 exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Painting and Sculpture: 1940-1970, as the perfect touchstone around which to organize a film. Using color film and future experimental filmmaker Ed Emschwiller as cinematographer, de Antonio filmed works of art in the exhibit itself. He arranged interviews with artists from Willem de Kooning to Kenneth Noland. De Antonio gave a more well-rounded picture of the art world by including interviews with notable critics Clement Greenberg and Hilton Kramer, major collectors Robert and Ethel Scull, and gallerist Leo Castelli.

While Geldzahler’s show contained both painting and sculpture, de Antonio focused on the painters, likely because he was already friendly with many of them. The film spans abstract expressionism to pop to color field painting, even including a female artist amongst the major figures of post-war machismo art scene: Helen Frankenthaler. Though Greenberg is provocative in his derision of pop art, the film mostly deals with artists well-established by 1972. A few more controversial interviews did not make it into the film, including an interview with sculptor Louise Nevelson and an interview with the Art Workers Coalition, a group that campaigned for more political art in museums and the inclusion of women and minority artists.

Along with Mitch Tuchman, de Antonio published a book version of Painters Painting in 1984, entitled Painters Painting: A Candid History of the Modern Art Scene, 1940-1970. Tuchman arranged transcripts of the original interviews into a collage organized by theme. This helpful resource is augmented by the collection’s extensive holdings of the original interview footage, offering a stunning window into the state of the New York art world circa 1970, seen through the eyes of its most successful denizens.

One uncompleted project that has received little attention is de Antonio’s book about powerful gallery owner Leo Castelli. Around the time the Painters Painting book was released, de Antonio signed a contract to write a book about Castelli and the art scene of the 1980s. Though de Antonio was generally disenchanted with the art scene, as paintings and sculptures fetched ever-more-astronomical prices, becoming more like investments than deeply-felt personal objects, he was still interested in the figure of Castelli. He conducted numerous interviews with his subject, property of the collection, but in 1985, he abruptly cancelled the project. De Antonio wrote a letter to Castelli, saying, “I find that the space between my politics and the art world is too great for me to write about it in the way I had hoped.”