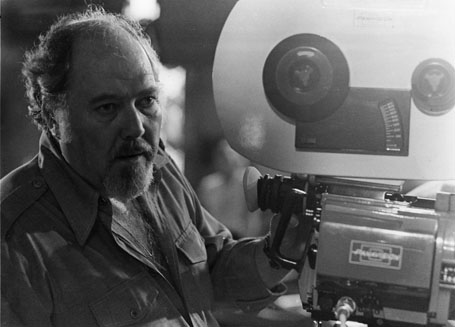

Robert Altman’s death in 2006 at the age of eighty-one brought an end to a remarkable filmmaking career that spanned almost sixty years. The surprise success of 1970’s M*A*S*H is often taken as a starting point for serious critical consideration of the maverick director’s career, but Altman had in fact been involved in filmmaking since he was cast as an extra in the 1947 Danny Kaye movie The Secret Life of Walter Mitty. Over the next twenty-five years Altman went from Hollywood extra to New Hollywood auteur, celebrated by East Coast film critics for his distinctive visual style and collaborative approach to moviemaking, as well as for his subversion of classic Hollywood genres in films like McCabe and Mrs. Miller and The Long Goodbye. The Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research’s collections document this remarkable transformation.

Altman’s early career can be divided into three distinct phases, and the WCFTR’s holdings provide unique documentation of each.

Kansas City

After receiving story credits for two films, Laurence Tierney’s 1948 film noir Bodyguard and the crime melodrama Christmas Eve, Altman left Hollywood to return to his hometown of Kansas City, Missouri. There, Altman began his directorial career at the Calvin Company, a producer of 16mm business and educational films. Though he intermittently returned to Hollywood to try his luck, Altman spent six years in Kansas City, working at Calvin and making independent films.

Television

On the strength of his independent teen exploitation film, The Delinquents, Altman was hired to direct Alfred Hitchcock Presents, then in its third season on CBS. Altman directed two well-received episodes of the show, but was removed from the production after a dispute with the show’s management over his script for the third episode. This set the pattern for much of Altman’s small screen career, during which he turned out more hours of television than any other director who made the transition from TV to theatrical film production.

New Hollywood Auteur

After almost a decade of work in the medium, Altman left television for feature filmmaking in the mid-sixties. He made two films, the sci-fi programmer Countdown and the independent psychodrama, That Cold Day in the Park, before he was hired by Ingo Preminger to direct M*A*S*H in 1969. Despite being, famously, the producer’s fifteenth choice to direct the film, Altman crafted both a critical and financial smash, winning the grand prize at Cannes and earning forty million dollars.

The success of M*A*S*H enabled Altman to begin a period of his career marked by prodigious output. He would make four films in the next three years (and nine more before the end of the decade). While none of these films matched the box office success of M*A*S*H, each built upon Altman’s critical reputation as a New Hollywood auteur. Altman came to be regarded as a director who dramatically subverted Hollywood genres and staked a claim for the status of visionary artist—a label usually reserved for European directors like Ingmar Bergman and Federico Fellini.

The Altman holdings at the WCFTR span multiple collections, including the papers of Patrick McGilligan, author of Robert Altman: Jumping off the Cliff, the United Artists Corporation, and documents donated by Altman relating to his work from 1969-1972.

References:

McGilligan, Patrick. Robert Altman: Jumping off the Cliff. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1989.

O’Brien, David. Robert Altman: Hollywood Survivor. New York: Continuum, 1995.

Thompson, David, ed. Altman on Altman. London: Faber and Faber, 2006.

This featured collection was researched and written by UW-Madison doctoral candidate and 2009 Jarchow fellow Mark Minett. Thanks to Stephen Jarchow, Michele Hilmes, Maxine Ducey, Dorinda Hartmann, Heather Heckman, and Liz Ellcessor.