Tanya Goldman

In this blog post, Tanya Goldman continues to examine materials from WCFTR’s Amos Vogel collection. Digitized materials discussed below – and many more! – are available on the Internet Archive thanks to a grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC). She previously wrote about using the Vogel papers here.

Among the Vogel papers at WCFTR are several undated informal summaries and indexes of Cinema 16’s screenings and activities during its storied history from 1947 to 1963. Early in one particular dossier of materials is a four-page, double-columned typewritten list titled “Among the Filmmakers Whose Work Was First Introduced to American Audiences at Cinema 16.” The list contains more than 215 filmmakers purported to have had some of their earliest U.S. screenings at Cinema 16. The list reads as a who’s who of luminaries now synonymous with mid-20th century foreign art, experimental, and independent cinema: from Michelangelo Antonioni to François Truffaut, Jordan Belson to Marie Menken, John Cassavetes to Shirley Clarke, among many, many others. The list is also populated with scores of names comparatively less remembered, some even forgotten.

As a tribute to the less remembered short films (and their filmmakers) showcased at Cinema 16, this post looks to Cinema 16’s first three programs in 1947-48, all screened multiple times at the Provincetown Playhouse in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village. In what follows, I reproduce large swaths of Cinema 16’s program notes distributed at (or, perhaps, prior to) Cinema 16 screenings, add my own additional production context (when applicable), and reflect on what types of works – particularly nonfiction – Vogel considered worthy of study in the years immediately following the Second World War.

Should this blog post and excerpts from Vogel’s program notes featured below pique your interest, you’re in luck! You can watch virtually all of these works online at your leisure. Get your popcorn ready!

In the spring of 1948, Amos Vogel published an explainer about his recently launched film society in the quarterly periodical Film News; two years later – with more screenings under his belt – he expanded upon these ideas in “Cinema 16: A Showcase for the Nonfiction Film” in Hollywood Quarterly (precursor to today’s Film Quarterly). In this latter essay, Vogel proclaimed that in less than three full years in operation, his humble “dream to create a permanent showcase for 16-mm. documentary and experimental films [had become] very much a reality.” He continued by noting that attendance at recent screenings – more than 3,000 viewers per show! – proved his original thesis: “that there were scores of superior nonfiction films gathering dust on film-library shelves” and an untapped audience “eager to see them.” Indeed, Cinema 16 quickly outgrew its original home, moving uptown to the Central Needle Trades Auditorium (today part of the High School of Fashion Industries). (Photocopies of both essays available here)

The Hollywood Quarterly article continues with an outline of Cinema 16’s approach to programming which centered “films that comment on the state of man, his world, and his crises, either by means of realistic documentation or through experimental techniques. It ‘glorifies’ nonfiction…[Cinema 16] hails a film that is a work of art, but will not hesitate to present a film that is important only because of its subject matter. Its avant-garde films comment on the tensions and psychological insecurity of modern existences or are significant expressions of modern art. Its social documentaries stimulate rather than stifle discussion and controversy.”

What I find particularly notable is how Vogel seems to elide “realistic documentation” (even at its most prosaic) and avant-garde/experimental practices in ways that anticipate Scott MacDonald’s formulation of the “avant-doc.” (Vogel would later write more theoretically about relations between documentary, the avant-garde, and cinematic truth in an unpublished 1953 essay recently published here). For my purposes here, suffice it to say, Vogel’s capacious framework for finding nonfiction value in an eclectic mix of films is evident throughout Cinema 16’s earliest program notes.

Vogel’s capacious framework for finding nonfiction value in an eclectic mix of films is evident throughout Cinema 16’s earliest program notes.

Program 1 (dated November 1947)

Screening Dates and Times: November 4, 5, 11, 12 at 7:45pm and 9:30pm

Extended excerpts and film credits as written in Vogel’s program notes (with brief annotations)

Glen Falls Sequence (Douglass Crockwell, 1946)

A non-objective film, concerned primarily with the intuitive expression of the artist through the play and hazard of the medium. The fluid imagery is left for each of us to interpret in our own way…” Streaming via YouTube here.

A non-objective film, concerned primarily with the intuitive expression of the artist through the play and hazard of the medium. The fluid imagery is left for each of us to interpret in our own way…” Streaming via YouTube here.

Monkey Into Man (Stuart Legg for Strand Films in England, under supervisor of biologist Julian Huxley, 1938)

Not by any means a truly comprehensive scientific study, this film nevertheless conveys in a popular fashion facts as to the development and habits of various types of apes. Skillful direction and entertaining comment almost succeed in transforming the film into an “entertainment” piece.

Not by any means a truly comprehensive scientific study, this film nevertheless conveys in a popular fashion facts as to the development and habits of various types of apes. Skillful direction and entertaining comment almost succeed in transforming the film into an “entertainment” piece.

[TG: Billed as a “Cinema 16 favorite,” Monkey Into Man screened again in the mid-1950s due to popular demand from members]

Streaming via Internet Archive here.

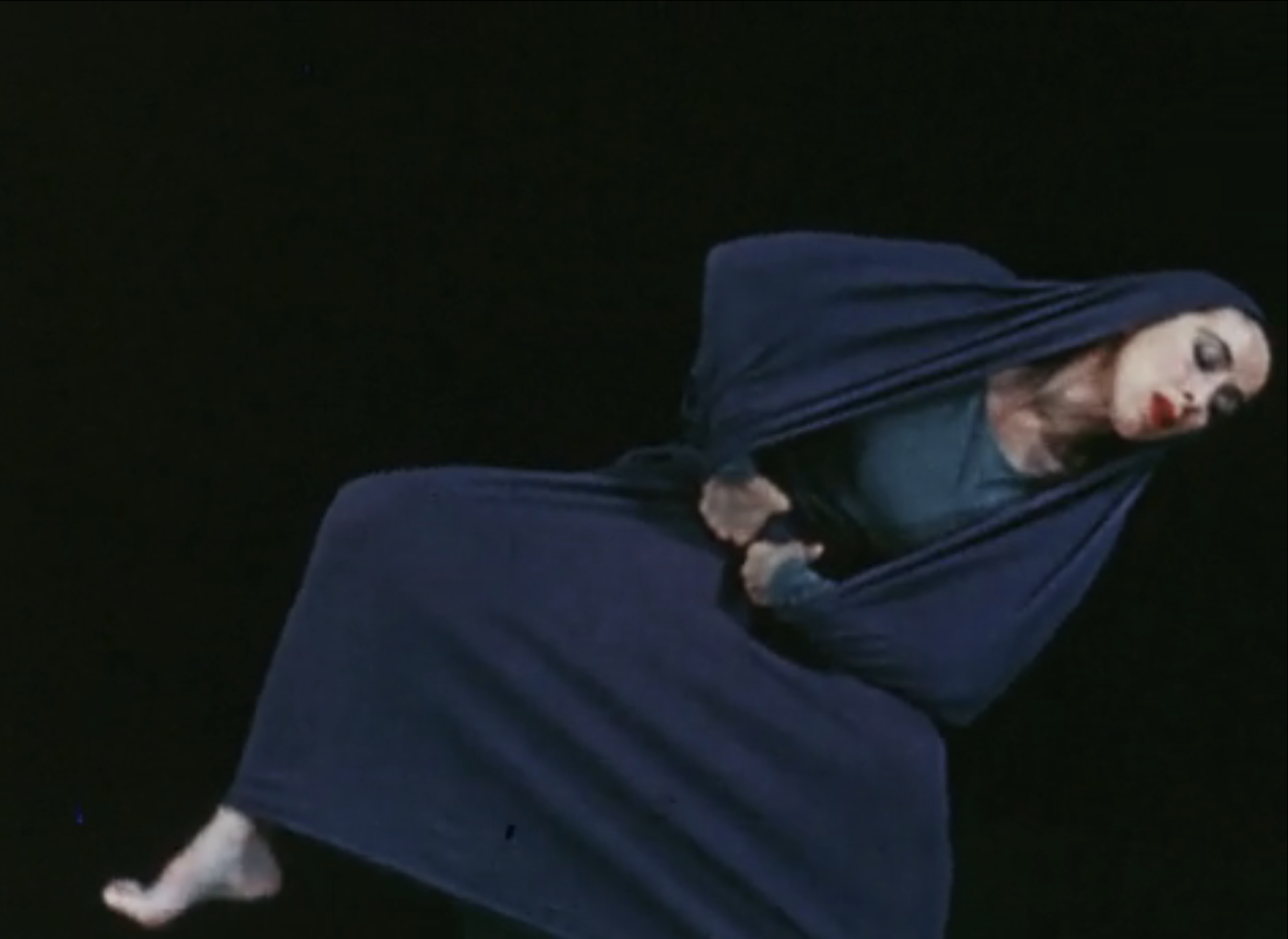

Lamentation (“Mr. and Mrs. Moselsio” for the Harmon Foundation, 1943)

This masterpiece of interpretative dance is done entirely from a sitting position, with repeated close-ups, revealing Martha Graham’s dance technique in great details. Because of its interesting movements and sculptural planes, the film should prove of interest not merely to students of the dance, but also to artists and sculptors.

This masterpiece of interpretative dance is done entirely from a sitting position, with repeated close-ups, revealing Martha Graham’s dance technique in great details. Because of its interesting movements and sculptural planes, the film should prove of interest not merely to students of the dance, but also to artists and sculptors.

[TG: Shot at Bennington College by Simon and Herta Moselsio of the Art Faculty. Film was released in 1943 though competing sources suggest it was filmed in the 1930s]

Streaming via Indiana University’s Media Collections website here.

The Potted Psalm (Written, produced, and directed by Sidney Peterson and James Broughton; photography by Sidney Peterson, 1946)

Shot in San Francisco during the summer of 1946, this film undertakes a visual penetration of the chaotic inner complexities of our post-war society, heretofore the preoccupation of serious modern writers. The film medium is potentially more natural one than literature in dealing with the sub-verbal realms of the subconscious since it is more analogous to the dream world and its imagery. But the contents of the dream world are divorced from rationality and possess a necessary ambiguity. Thus the only possible approach to a film of this sort — indeed, in a sense, any work of art — is to accept the ambiguity without interjection of the question: Why? Since we all possess an infinite university of ambiguity within us, these images are meant to play upon that world, and not our rational senses….

Shot in San Francisco during the summer of 1946, this film undertakes a visual penetration of the chaotic inner complexities of our post-war society, heretofore the preoccupation of serious modern writers. The film medium is potentially more natural one than literature in dealing with the sub-verbal realms of the subconscious since it is more analogous to the dream world and its imagery. But the contents of the dream world are divorced from rationality and possess a necessary ambiguity. Thus the only possible approach to a film of this sort — indeed, in a sense, any work of art — is to accept the ambiguity without interjection of the question: Why? Since we all possess an infinite university of ambiguity within us, these images are meant to play upon that world, and not our rational senses….

[TG: Also billed as a “Cinema 16 favorite” and would screen again in the mid-1950s due to popular demand!]

Streaming via YouTube

Boundary Lines (Animation by Philip Stapp. Music by Gene Forrell, 1945)

This outstanding cartoon successfully combines a social message with unique color animation, provocative commentary, and a distinguished musical score.

This outstanding cartoon successfully combines a social message with unique color animation, provocative commentary, and a distinguished musical score.

[TG: Produced by prolific documentary filmmaker and producer Julien Bryan]

Streaming via Indiana University’s Media Collections website here.

Program 2 Notes (December 1947)

Screening Dates and Times: December 2, 3, 9, 10, 16, 17 at 7:45pm and 9:30pm

Extended excerpts and film credits as written in Vogel’s program notes (with brief annotations where indicated)

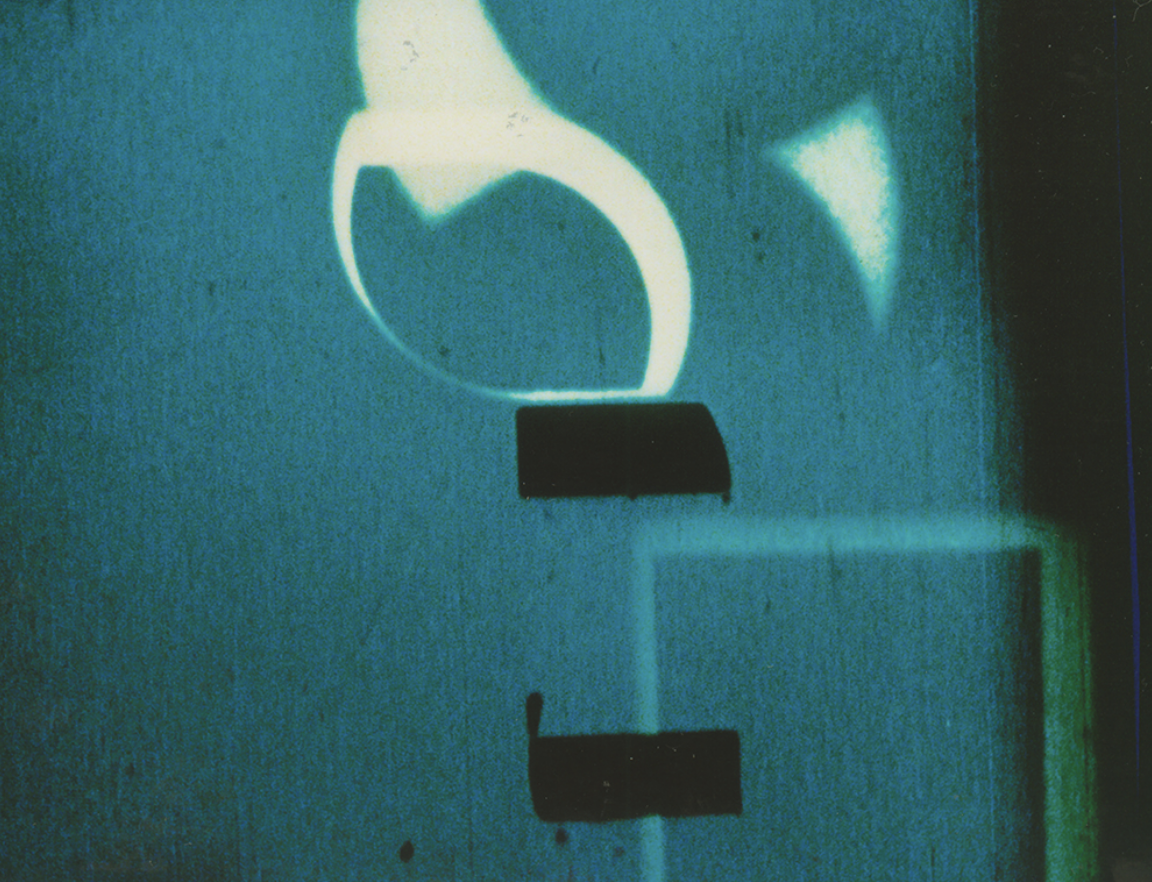

Abstract Film Exercises

Produced 1943/44 by John and James Whitney (Guggenheim fellowship).

The basic aim of the Whitney Brothers is to explore the possibilities of dynamic color relationships and sound production toward the development of an abstract film art form. Their brilliant color animations are created by a modified optical printer, paper cutouts, and filters. Much like a musical theme, a visual pattern is first stated and then “developed” graphically by treating it to various moods of color and motion…Their weird tonal patterns are created by no known instrument, but by a specifically designed machine which in itself is sound-less, and merely regulates the shape of a light ray. This light ray is then thrown directly onto the sound track, creating a distinct and “test tube” originated sound pattern…It is by virtue of this coldly scientific integration of sound and image that the film delivers their striking bi-sensory impact upon the observer.

The basic aim of the Whitney Brothers is to explore the possibilities of dynamic color relationships and sound production toward the development of an abstract film art form. Their brilliant color animations are created by a modified optical printer, paper cutouts, and filters. Much like a musical theme, a visual pattern is first stated and then “developed” graphically by treating it to various moods of color and motion…Their weird tonal patterns are created by no known instrument, but by a specifically designed machine which in itself is sound-less, and merely regulates the shape of a light ray. This light ray is then thrown directly onto the sound track, creating a distinct and “test tube” originated sound pattern…It is by virtue of this coldly scientific integration of sound and image that the film delivers their striking bi-sensory impact upon the observer.

[TG: Cover of program indicates five abstract exercises. I have only been able to locate four online. Exercise 4 was another “Cinema 16 favorite” that would screen again in the mid-1950s due to popular demand]

Exercises 1-4 streaming on YouTube: Exercise 1, Exercises 2-3, and Exercise 4.

The Feeling of Rejection

The case history of a young women who learned in childhood not to risk disapproval by taking independent action. Childhood events that created a crippling fear of failure are recapitulated; the causes and harmful effects of her inability to engage in normal competition are then analyzed. Notwithstanding its seemingly unpretentiousness and use of non-professional actors, this film succeeds admirably in making a psychological program come alive. Mature commentary and skillful dramatization create an arresting visualization of adjustment problems. Produced 1947 by the Canadian Film Board.

The case history of a young women who learned in childhood not to risk disapproval by taking independent action. Childhood events that created a crippling fear of failure are recapitulated; the causes and harmful effects of her inability to engage in normal competition are then analyzed. Notwithstanding its seemingly unpretentiousness and use of non-professional actors, this film succeeds admirably in making a psychological program come alive. Mature commentary and skillful dramatization create an arresting visualization of adjustment problems. Produced 1947 by the Canadian Film Board.

[TG: Produced in 1947 by National Film Board of Canada on behalf of the Mental Health Division of the Department of National Health and Welfare in Ottawa; directed by Robert Anderson. Number 1 in series on ‘mental mechanisms’]

Streaming via National Film Board of Canada website here.

And So They Live

Moving in its simplicity, yet filled with a certain poetic realism, this film by John Ferno is in the best documentary film tradition: to portray life truthfully and realistically, to use the actual locale rather than the studio, to use people engaged in their daily tasks instead of professional actors. The camera pierces their harsh and cheerless lives, condemns by mere portrayal antiquated farming methods, the overcrowded and understaffed school, and a curriculum divorced from the life of the children. Refreshing is also Mr. Ferno’s refusal to end on an optimistic note or to provide an artificially contrived solution. Instead, the fade-out conveys at one time both the warmth of family relations as well as the unrelieved poverty of these people.

Moving in its simplicity, yet filled with a certain poetic realism, this film by John Ferno is in the best documentary film tradition: to portray life truthfully and realistically, to use the actual locale rather than the studio, to use people engaged in their daily tasks instead of professional actors. The camera pierces their harsh and cheerless lives, condemns by mere portrayal antiquated farming methods, the overcrowded and understaffed school, and a curriculum divorced from the life of the children. Refreshing is also Mr. Ferno’s refusal to end on an optimistic note or to provide an artificially contrived solution. Instead, the fade-out conveys at one time both the warmth of family relations as well as the unrelieved poverty of these people.

Produced by the Educational Film Institute of New York University. Directed by John

[TG: Shot in Kentucky in 1940, sponsored by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. John Ferno was born John Fernhout in the Netherlands and previously worked with Joris Ivens; unclear why Vogel does not attribute film to co-director Julian Roffman within his description.]

Streaming via Film Preservation.org’s Screening Room here.

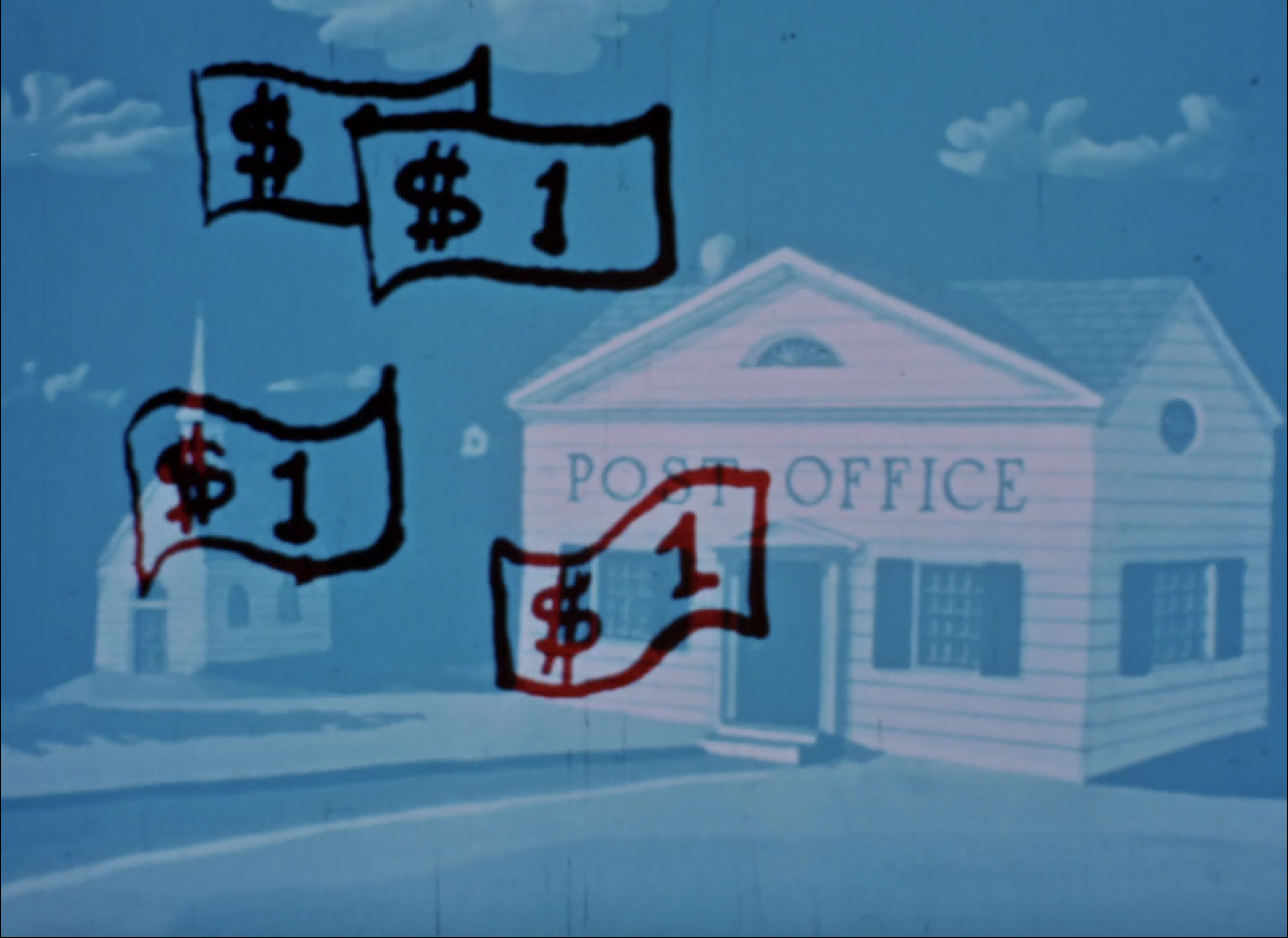

Hen Hop

Five for Four

These unusual and captivating color animations by the Canadian artist Norman McLaren were made in 1945 as reminders of various war savings campaigns. While their message is dated, their artistry has remained vibrantly alive. Contrary to the usual animation techniques which call for the photographing of cut-outs or drawings, McLaren handpaints directly on the negative film, frame by frame. The result of his artistic ingenuity and painstaking labor has been an exuberant mixtures of color, sound, and images.

Both Hen Hop and Five for Four (both released in 1942 according to NFBC) are streaming via the National Film Board of Canada website, as are dozens of other works by Norman McLaren!

Program 3 Notes (January 1948)

Screening Dates and Times:

January 12, 19, 21, 28 at 7:45pm and 9:30pm

January 24 and 25 at 2:00pm, 3:45pm, 5:30pm

Extended excerpts and film credits as written in Vogel’s program notes (with brief annotations where indicated)

Your Children and You

(Produced by Alex Shaw for Realist Film Unit, England. Camera: A.E. Jeakins. Music: William Alwyn.)

Whether or not you have children you will chuckle when you see this film. Instead of assuming a dry textbook attitude, it utilizes imaginative photography, a crisp commentary and well-selected incidents to create an amusing “entertainment” piece. Of interest is also its attempt to portray the subject as seen through the eyes of the child. While many suggestions offered in the film are genuinely helpful, others are not entirely in accordance with present day educational methods

Whether or not you have children you will chuckle when you see this film. Instead of assuming a dry textbook attitude, it utilizes imaginative photography, a crisp commentary and well-selected incidents to create an amusing “entertainment” piece. Of interest is also its attempt to portray the subject as seen through the eyes of the child. While many suggestions offered in the film are genuinely helpful, others are not entirely in accordance with present day educational methods

[TG: Produced by Central Office of Information Film for the Ministry of Health in cooperation with the Central Council for Health Education in 1946. Direction credited to Brian Smith].

Streaming via London’s Wellcome Collection online museum and library here.

Underground Farmers

This remarkable scientific film reveals by means of brilliant photography intimate details of the live and social organization of a unique ant society in Equatorial South America. Extreme close-ups and explicit commentary are effectively utilized to present the unusual underground mushroom plantations, methods of cultivation, division of labor, and finally, a battle between two warring ant colonies. A Van Beuren Production.

This remarkable scientific film reveals by means of brilliant photography intimate details of the live and social organization of a unique ant society in Equatorial South America. Extreme close-ups and explicit commentary are effectively utilized to present the unusual underground mushroom plantations, methods of cultivation, division of labor, and finally, a battle between two warring ant colonies. A Van Beuren Production.

[TG: Released in 1936 through RKO; perhaps the last production released by the Van Beuren Corporation, a cartoon and short film producer, prior to closure.]

Streaming via Internet Archive here.

Seeds of Destiny

Produced by U.S. Army Signal Corps for UNRRA

A 1946 Academy Award Winner as “best documentary film of the year,” this bitter and tragic film on the plight of children in Europe is a fitting counterpart to YOUR CHILDREN AND YOU; its harrowing scenes demonstrate that to raise children properly, proper conditions of existence are as much needed as “correct” educational methods. It is neither a refined nor a pretty picture; it graphically depicts a reality which is coarse and shocking. This film was originally rejected by the American Theatre Association as “too gruesome and horrifying” for theatrical showing. CINEMA 16 is proud to present it.

Streaming via U.S. National Archives website here.

Fragment of Seeking

Conceived, directed, and photographed in 1946 by Curtis Harrington.

Interesting attempt at a quasi-poetical treatment of one boy’s adolescent yearning. The seeming realism of the film is deceptive – only its generalized symbolism is real. An atmosphere of foreboding prevails throughout and mounts work at times unusual…every aspiring amateur should note that this film was made with inexpensive 16mm “home movie” equipment and photographed in three days. Mr. Harrington, calling it a “documentary of the soul,” has provided an interesting note on the film which becomes fully intelligible only after one has seen it: “This is a cinematic portrait, a fragment of existence of the adolescent Narcissus. In reality of this true Narcissus we find not the arrogant, beautiful creature of the legend, but rather the questioning seeker, not wholly understanding the nature of his desire – until the final, overpowering revelation. The continuity of time reveals the image of desire, always there, just beyond. And then, in the moment of fulfillment, the image of death precipitates the truth.” Streaming via YouTube here.

Interesting attempt at a quasi-poetical treatment of one boy’s adolescent yearning. The seeming realism of the film is deceptive – only its generalized symbolism is real. An atmosphere of foreboding prevails throughout and mounts work at times unusual…every aspiring amateur should note that this film was made with inexpensive 16mm “home movie” equipment and photographed in three days. Mr. Harrington, calling it a “documentary of the soul,” has provided an interesting note on the film which becomes fully intelligible only after one has seen it: “This is a cinematic portrait, a fragment of existence of the adolescent Narcissus. In reality of this true Narcissus we find not the arrogant, beautiful creature of the legend, but rather the questioning seeker, not wholly understanding the nature of his desire – until the final, overpowering revelation. The continuity of time reveals the image of desire, always there, just beyond. And then, in the moment of fulfillment, the image of death precipitates the truth.” Streaming via YouTube here.

…And There’s More Short Films Awaiting Rediscovery!

As Cinema 16 grew, the production value of its program schedules increased. 1947-48’s simple flyers evolved into multi-page colorful trifolds and booklets with pleasing designs featuring 16mm reels and film strips. Cinema 16 also grew and expanded its programming. Special events became regular perks of membership. For example, the 1952/53 season alone featured appearances by Jean Renoir (presenting his “panned by critics” Rules of the Game), film critic Archer Winsten (screening and discussing Dreyer’s “neglected” Day of Wrath) and documentarian Sidney Meyers (director-writer-editor of Academy Award-winning documentary The Quiet One [1948]).

Even as Cinema 16 grew in size and stature, its commitment to screening (and later distributing) eclectic moving image content remained constant. Its approach to nonfiction, in particular, stubbornly defies today’s accepted documentary canon. A quick survey of Cinema 16’s programs in the 1950s and early ‘60s certainly finds references to the expected — Flaherty, Franju’s Blood of the Beasts and several works in the Griersonian tradition — as well as acclaimed, yet less remembered, documentarians like Arne Sucksdorff. At the same time, carefully examining programs also unearths additional medical films and numerous other modes and examples of useful cinema awaiting further discovery. For those interested in diversifying their cinematic palate and broadening their understanding of film history, take inspiration from Cinema 16’s programs, gifts from Amos Vogel that inspire discovery more than sixty years after Cinema 16 closed its doors.

For more on programming at Cinema 16, I highly recommend Scott MacDonald’s essay “Film Comes First,” published in Be Sand, Not Oil: The Life and Work of Amos Vogel, edited by Paul Cronin.

Tanya Goldman is a Research Fellow at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. She earned her Ph.D. in Cinema Studies in 2022 from New York University.

WCFTR has recently processed the Amos Vogel papers as part of the project “Expanding Film Culture’s Field of Vision: Processing and Sharing the Collections of Amos Vogel, Jump Cut, Angles, and the Wisconsin Film Festival,” funded by a grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission.