Introduction

In many ways, Dalton Trumbo’s story is a truly American one. Overcoming his humble roots, Trumbo rose to the top of his profession, becoming one of Hollywood’s most sought after and highly paid screenwriters in the process. But Trumbo’s livelihood would be stripped from him when he, like hundreds of other Hollywood screenwriters, actors, directors, and composers, was blacklisted because of his political beliefs. Trumbo, though, would fight to regain his professional stature, thereby disproving F. Scott Fitzgerald’s famous aphorism that there are “no second acts in American lives.” Working tirelessly to end the blacklist, Trumbo would eventually become the biggest symbol of its failure. By the end of 1960, Trumbo’s adaptations of Spartacus and Exodus topped U.S. box offices, and the screenwriter himself would come to epitomize America’s most precious freedoms.

Trumbo was born in 1905 in Montrose, Colorado. His father worked odd jobs as collection agent, constable, and shoe clerk, before eventually moving the family to California in 1924. After relocating to Los Angeles, Trumbo was forced to support his mother and siblings when his father fell ill and eventually died of pernicious anemia at age fifty-one. He took a job at the Davis Perfection Bakery. It always was intended to be a temporary job—a stopgap until he established himself as a writer—but it ended up lasting eight years. Trumbo had begun writing prior to his father’s death, and he was prolific, if not always good. As he recalled in 1940, during the time he worked at the bakery, Trumbo had written “eighty-eight short stories and six novels, all rejected.”

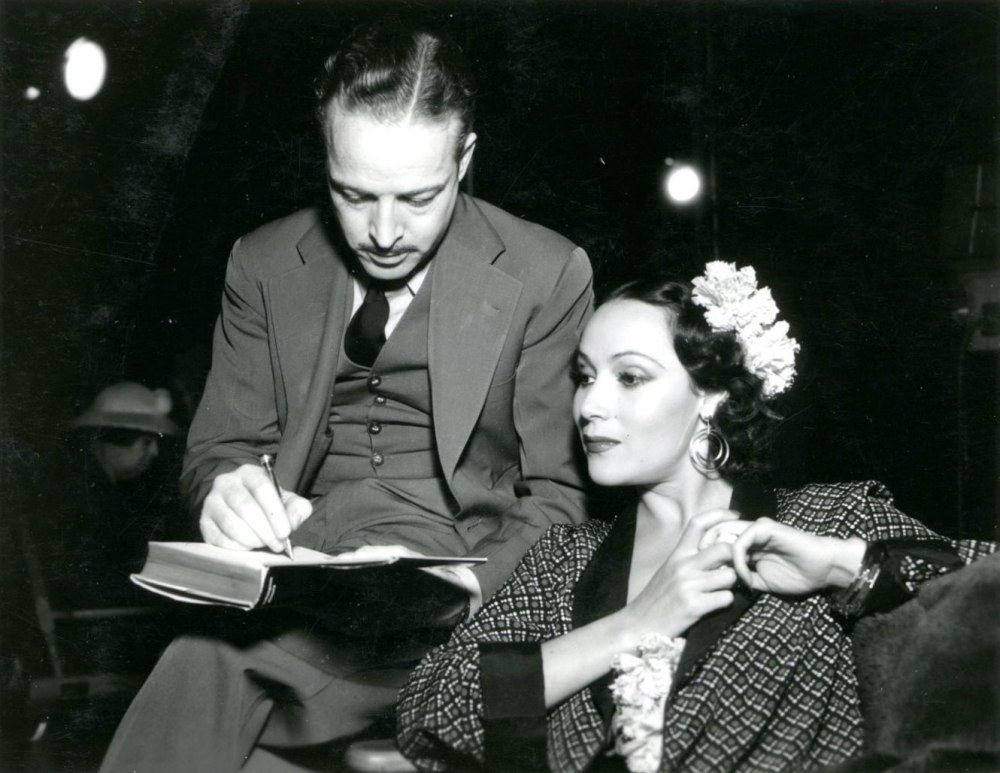

After publishing his first novel, Eclipse, as well as a handful of short stories in magazines, such as Vanity Fair and The Saturday Evening Post, Trumbo signed a contract with Warner Bros. in 1935, joining the studio as a screenwriter. His first assignments were for Bryan Foy’s B-unit, and although much of his early work was undistinguished, Trumbo spent the remainder of the decade working at Columbia, 20th Century-Fox, and RKO, signing a contract with the latter in 1938. A year later, Trumbo’s literary reputation would be cemented by the publication of his stunning anti-war novel, Johnny Got His Gun.

In 1941, just months after winning an American Booksellers Award for Johnny Got His Gun, Trumbo earned an Oscar nomination for the screenplay of Kitty Foyle. The film catapulted him to the A-list of Hollywood screenwriters and allowed him to sign a new contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, which, at the time, was the glitziest studio in town. Trumbo’s MGM output included several notable titles, such as A Guy Named Joe (1943), Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo (1944), and Our Vines Have Tender Grapes (1945). The latter is a nostalgic portrait of a small, rural farming town set in the fictional town of Fuller Junction, Wisconsin. Although the film is episodic and sentimental, it also is a tribute to the social bonds that unify a community, showing how collective responsibility and concern for our fellow citizens help to sustain us through both good times and bad. Indeed, if your heart doesn’t melt when young Selma, played by Margaret O’Brien, offers her beloved calf to a neighboring farmer whose barn and livestock were destroyed in a fire, well then you are made of much sterner stuff than me. At a time when agribusiness and factory farming have become the norm, Our Vines Have Tender Grapes is a welcome reminder of the shared values that allowed family farms to flourish as the “breadbasket” of the American economy.

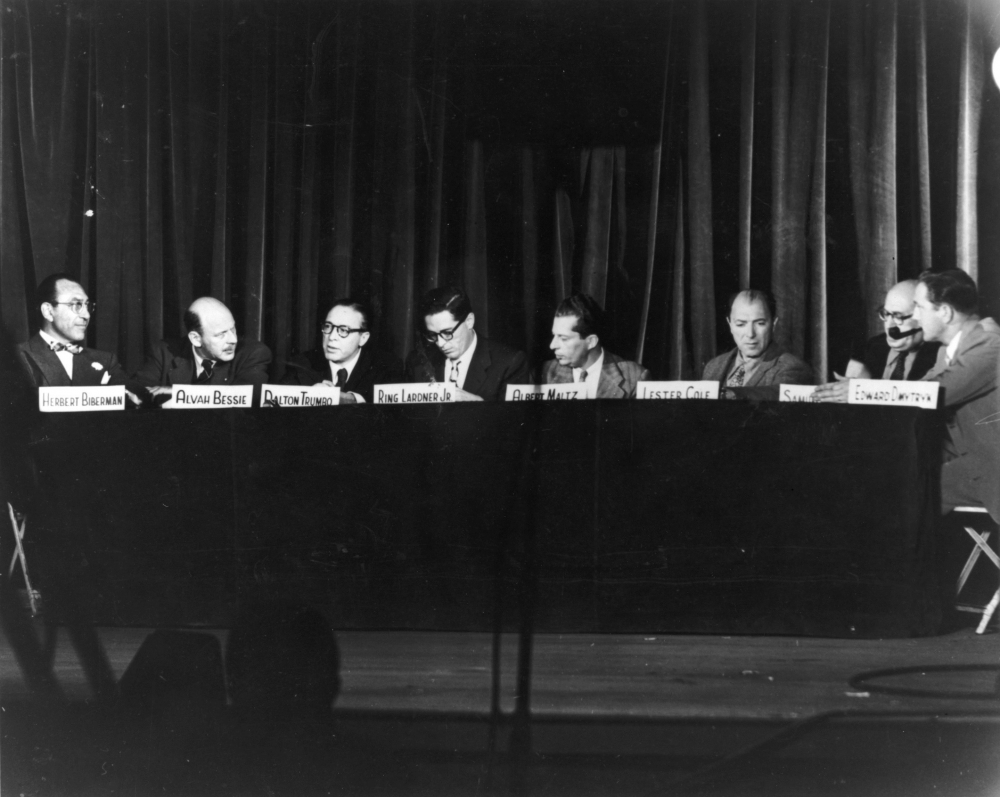

These communitarian values—and the film’s veiled appeals to the potential benefits of collective ownership—would make Trumbo a marked man just a few years later. A longtime member of the Communist Party, Trumbo was among the eleven “unfriendly” witnesses that testified before the House Committee on Un-American Activities in October of 1947. During the hearings, Lela Rogers, one of several “friendly” witnesses aiding HUAC’s inquiry into Communist subversion of Hollywood films, claimed that her daughter Ginger believed Trumbo had put Red propaganda into her mouth during the shooting of Tender Comrade. The film, which tells the story of four “Rosie the Riveter” types who agree to rent a house together, raised Rogers’s hackles during a scene in which the women agree to “run the joint like a democracy” on a “share and share alike basis.”

Although HUAC was hard-pressed to find anything else objectionable in the hundreds of pages of script material churned out by Trumbo, his refusal to answer the Committee’s questions earned him a Contempt of Congress citation along with nine other screenwriters, producers, and directors identified as suspected Communists. Soon after, the studios collectively announced that they would discharge the various members of the “Hollywood Ten” and further that they would not knowingly employ any member of the Communist Party.

When Trumbo was fired by MGM, he was earning a fee of $75,000 per script or $3,000 per week for as long as he was needed to complete a job. With significant debts and little prospects for work, Trumbo took an assignment offered him by the King Brothers, earning a mere $3,750 for eighteen months of work writing the screenplay for Gun Crazy (1950). Using fronts and pseudonyms, Trumbo spent the next decade spinning out scripts for independent producers. Indeed, during his time on the black market, Trumbo did some of his best work, adding films like He Ran All the Way (1950), The Prowler (1951), and Roman Holiday (1953) to an already impressive corpus of pre-blacklist work. Operating in the industry’s shadows, Trumbo’s work won two Oscars, even though he didn’t actually receive those awards until decades afterward.

The second of these awards was for an original story Trumbo wrote under the pseudonym of “Robert Rich,” and when no one stepped forward to claim the Oscar during the ceremonies, speculation ran rampant that it was really the work of a blacklisted writer. Recognizing that the press’ interest in the Rich affair created an opportunity to expose the blacklist’s failure, Trumbo refused to either confirm or deny that he was the mysteriously missing Oscar winner. Instead, Trumbo acknowledged his black market work saying that it enabled him to distance himself from some of the “stinkers” he wrote and yet get credit for the success of titles with which he had no real connection.

The Rich affair—and the Oscars won by other blacklisted writers—created a public relations nightmare for Hollywood. Not only did it show that the studios’ pledge not to employ Communists had proven false, but it also suggested that the audience couldn’t trust any screenwriter credit that appeared onscreen. More important, it implicitly questioned the need for the blacklist in the first place. After all, if Robert Rich’s Disneyesque “Boy and bull” story for The Brave One merited Oscar consideration, just how subversive could it, and the other films written by blacklisted screenwriters, really be?

Due to the industry pressures created by the public exposure of the black market, Trumbo believed the blacklist was ready to crumble and that either he or one of his fellow black market writers, Albert Maltz and Michael Wilson, were poised to finally get screen credit under his own name. In offering hope that the blacklist would eventually end, Trumbo likely recognized that the traits that earned him his reputation in the 1940s, namely his talent and work ethic, were the same traits that would regain his name years later.

When Trumbo signed a contract with Kirk Douglas’s Bryna Productions to rewrite a first draft of the screenplay for Spartacus under the pseudonym “Sam Jackson,” the groundwork was laid for Trumbo to reclaim his place as one of Hollywood’s top screenwriters. Although anti-communism remained an important part of political life, public sentiment had generally turned against the blacklist itself. When Universal-International released Spartacus with the credit “Screenplay by Dalton Trumbo,” U.S. film critics argued that its depiction of the thirst for freedom was as American as baseball, Mom, and apple pie. Moreover, when President John F. Kennedy attended a showing of Spartacus on the recommendation of his brother, Bobby, the public gesture dampened the spirit of whatever protest remained. As Helen Manfull observed in Additional Dialogue, her edited collection of Dalton Trumbo’s letters, the former political pariah believed “the incident was not accidental, and admired the President for it.”

In April of 1961, the Teacher’s Union honored Trumbo with an award that celebrated his enrichment of American life through his “creative gifts as a writer and stalwart stand against the Un-American blacklist.” Ironically, the ceremony took place at the same Waldorf Astoria Hotel where the major studios declared Trumbo an enemy of democracy just thirteen years earlier. For Trumbo, the validation of his career must have seemed bittersweet. In his own mind, neither he nor his approach to screenwriting had changed since 1947. Still Trumbo was astute enough to appreciate the irony in the fact that the same rhetoric used to prosecute him during the Cold War (i.e. the fight for freedom against tyranny) was now invoked to identify him as a champion of free speech.

The items in the WCFTR’s Dalton Trumbo collection and the new film about Trumbo’s life, starring Bryan Cranston, all serve as reminders of this grim period in America’s recent history and as a warning of its potential recurrence. Today, when Wisconsin residents hear the name “McCarthy,” they are much more likely to think of the Green Bay Packers’ head coach than they are the junior senator nicknamed “Tail Gunner Joe.” But just when you think it couldn’t happen again, along comes a politician like Michelle Bachmann who suggested in 2008 that the media should investigate members of Congress in order to uncover their anti-American beliefs. As someone who never stopped fighting, Trumbo’s story is one of grit, resilience, and hope. But it is also a cautionary tale about the dangers of political repression, one that vividly demonstrates the famous dictum that eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.

Jeff Smith

Professor of Communication Arts

Director of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research

University of Wisconsin-Madison

Terms of Use for the Collection

The WCFTR provides the information contained in this collection for non-commercial, personal, or research use only. Any other use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly reproductions, redistribution, publication or transmission, whether by electronic means or otherwise, without prior written permission of the copyright holder is strictly prohibited.