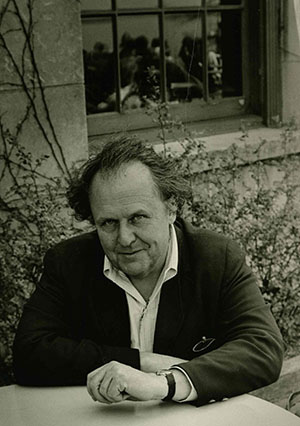

Emile de Antonio (1919-1989) was a radical American documentary filmmaker during the Cold War years, a remarkably fertile period of both independent filmmaking and political dissent. He specialized in political documentaries with a compilation style, cobbling together television footage, interviews, and other audio-visual material to argue his point. Not trained as a filmmaker, de Antonio nonetheless dedicated the greater part of his life to exploring and expressing his viewpoint on historical topics close to his heart. He passionately covered the major touchstones of post-war America, including the McCarthy hearings, the assassination of JFK, the Vietnam War, and the character of Richard M. Nixon. In the process, he found himself under surveillance by the FBI and subpoenaed by the Department of Justice.

But de Antonio was no zealous outsider; he kept up friendships with artists, intellectuals, and New York power brokers. It is from this pool of wealthy, liberal friends that de Antonio was able to finance his films. He took great pleasure in persuading investors to commit to his film projects, and he fought equally hard to pay them back, even though the market for documentaries was nascent and uncertain. His first film, Point of Order, was a surprise success at the box office, and throughout his career, he experimented with various ways of distributing and exhibiting his films. However, as a politically committed filmmaker, de Antonio was often torn between his desire for financial success, which could help him make more films, and his desire to use his films to benefit progressive causes.

Not only did de Antonio make films in a modernist style, he befriended and mentored a cadre of modernist painters in the New York School. One of his closest friendships was with Andy Warhol, who credited de Antonio with helping him become a painter. De Antonio was also a force in the lives of young artists Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns in the 1950s and 1960s as they began to change the vanguard of art completely. Although he distributed the seminal Beat film Pull My Daisy and signed their manifesto in 1962, de Antonio was not at the center of the New American Cinema group and Film-makers’ Cooperative alongside Jonas Mekas, Shirley Clarke, Stan Brakhage, and Gregory Markopoulos. Nevertheless, de Antonio was dedicated to independent film and was instrumental in the careers of a number of young filmmakers, including Dan Drasin and Ron Mann.

The Emile de Antonio Collection at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research is the most comprehensive personal collection of an independent filmmaker working in this period of cinematic and political rebellion. The collection contains a wealth of business records and correspondence about the production and distribution of all de Antonio’s completed works, as well as about his many uncompleted films and books. These materials offer a complete picture of the business of independent film production and distribution from the 1960s through the 1980s.

The collection also includes pamphlets for political organizations that de Antonio belonged to, film treatments sent to the director in hopes of guidance or patronage, publicity cards from various New York City art galleries, and personal correspondence with numerous guiding lights from the overlapping worlds of filmmaking, art, and New Left politics. The WCFTR solicited de Antonio’s papers in the middle of his career in the interest of archiving the work of socially active filmmakers. Recently reprocessed with the help of a grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Committee (NHPRC), the collection has been organized for ease of research, highlighting de Antonio’s film career, political activism, and art world connections. Click here to view the online finding aid.

This featured collection was researched and written by UW-Madison doctoral candidate and Jarchow fellow Nora Stone. Thanks to Stephen Jarchow, Vance Kepley, Emil Hoelter, Maxine Ducey, Mary Huelsbeck, and Michael Trevis.