In de Antonio’s film about the Vietnam Wars (plural), the director lays bare the political systems and capitalist machine that led to America’s involvement in the quagmire. In the Year of the Pig is not a film about people, but about systems, and how these systems led to a war that was damaging for all except the chemical and mechanical manufacturers who benefit from armed conflict. The film connects the bloody dots between politicians and business leaders, Western imperialists, and puppet governments, using a collage of rare archival footage from the French colonial period, film dispatches from the current conflict, and interviews with American policymakers and international experts on Vietnam. Completed in 1969, in the thick of both the undeclared war and the growing anti-war movement, Pig is an explosive analysis of the American war machine and the Vietnamese independence movement it tried to hobble.

In de Antonio’s film about the Vietnam Wars (plural), the director lays bare the political systems and capitalist machine that led to America’s involvement in the quagmire. In the Year of the Pig is not a film about people, but about systems, and how these systems led to a war that was damaging for all except the chemical and mechanical manufacturers who benefit from armed conflict. The film connects the bloody dots between politicians and business leaders, Western imperialists, and puppet governments, using a collage of rare archival footage from the French colonial period, film dispatches from the current conflict, and interviews with American policymakers and international experts on Vietnam. Completed in 1969, in the thick of both the undeclared war and the growing anti-war movement, Pig is an explosive analysis of the American war machine and the Vietnamese independence movement it tried to hobble.

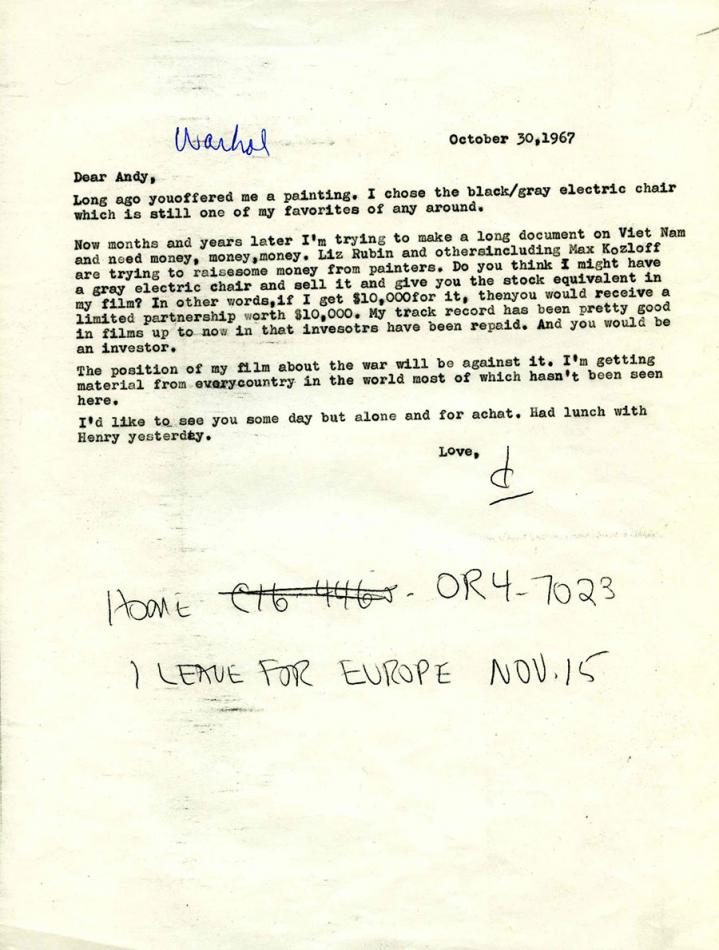

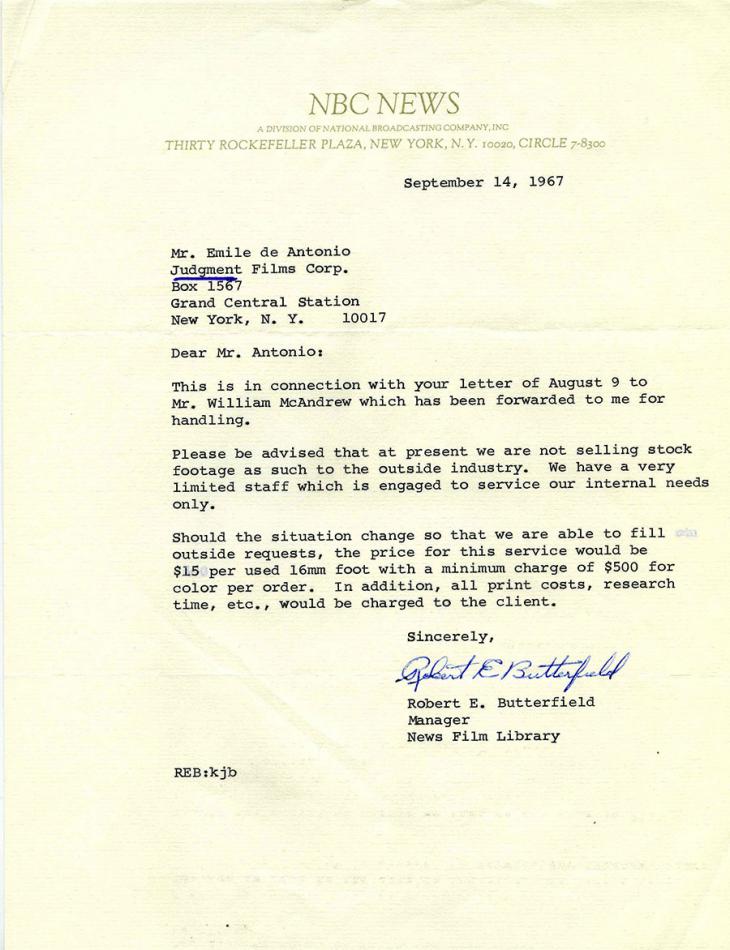

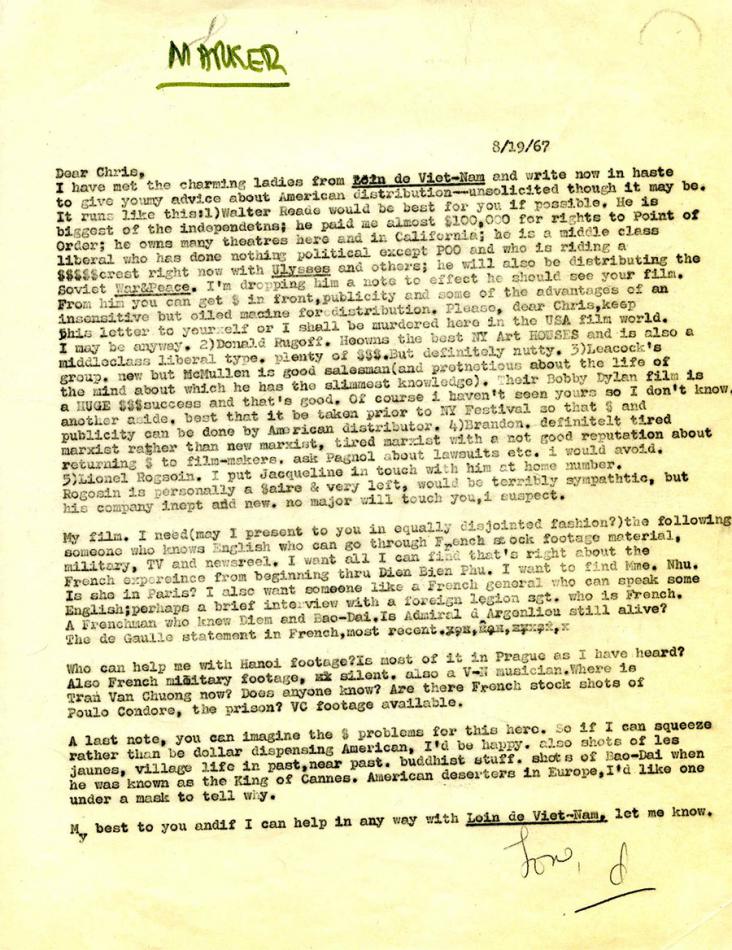

For this film, de Antonio educated himself on the history of Vietnam, looking far back before the United States intervened in southeast Asia. While the official story started with supposed North Vietnamese attacks on the USS Maddox and USS Turner Joy in the Gulf of Tonkin, de Antonio was committed to showing the long history of Western aggression in the region. He claimed to have read 200 books to prepare for production, and the folders are stuffed with handwritten notes about plans for the film. He traveled all over to world to find footage never before seen in the United States, in order to show his audience a different view of Vietnam than that propagated by the American media. De Antonio also interviewed congressmen like anti-war proponent Senator Thruston B. Morton, American servicemen, and experts on Vietnam, such as Jean Lacouture and Yale University professor Paul Mus. The collection includes voluminous correspondence between the director and his interviewees, as well as sheets of paper on which de Antonio constructed the film’s script by piecing together bits of interview transcriptions.

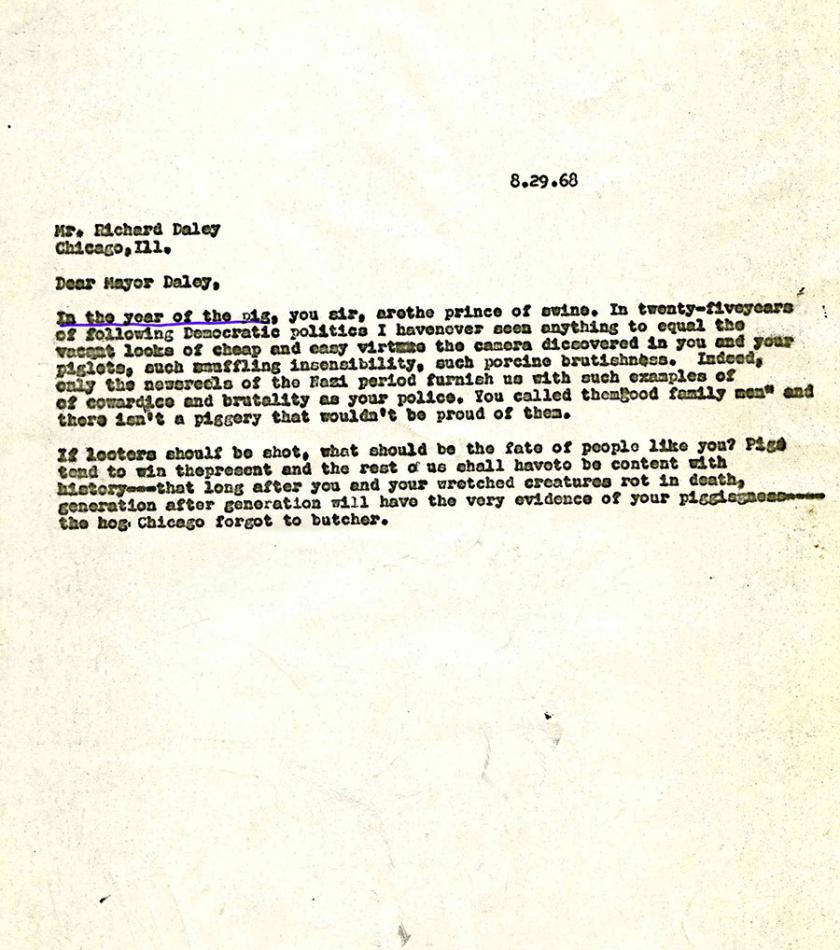

After the distribution problems Rush to Judgment ran into, de Antonio told Variety that he would mainly distribute Pig to college campuses, rather than through commercial theatres. Pathe-Contemporary, a division of educational media conglomerate McGraw-Hill, handled all bookings. Though de Antonio had wanted the film to premiere during the infamous 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, the film wasn’t ready by August. The name also came to be seen as a reference to “pigs,” the epithet thrown at Chicago policemen, but in a sardonic note to Mayor Richard Daley (as seen above), de Antonio assured him this was not the case. When it was finished, the film premiered in a number of cities as a benefit for anti-war groups like Resist, Clergy and Laymen Concerned, and the Chicago 7. In spite of de Antonio’s desire to use the film for fundraising and consciousness-raising, he angrily decried Newsreel Collective’s unauthorized use of Pig on U.S. military bases in Germany. Herein lies de Antonio’s conundrum: he was an independent thinker caught between mainstream media, which he deemed fluffy and apolitical, and radical collectivist filmmaking practices, which he considered amateurish and irresponsible.

After the distribution problems Rush to Judgment ran into, de Antonio told Variety that he would mainly distribute Pig to college campuses, rather than through commercial theatres. Pathe-Contemporary, a division of educational media conglomerate McGraw-Hill, handled all bookings. Though de Antonio had wanted the film to premiere during the infamous 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, the film wasn’t ready by August. The name also came to be seen as a reference to “pigs,” the epithet thrown at Chicago policemen, but in a sardonic note to Mayor Richard Daley (as seen above), de Antonio assured him this was not the case. When it was finished, the film premiered in a number of cities as a benefit for anti-war groups like Resist, Clergy and Laymen Concerned, and the Chicago 7. In spite of de Antonio’s desire to use the film for fundraising and consciousness-raising, he angrily decried Newsreel Collective’s unauthorized use of Pig on U.S. military bases in Germany. Herein lies de Antonio’s conundrum: he was an independent thinker caught between mainstream media, which he deemed fluffy and apolitical, and radical collectivist filmmaking practices, which he considered amateurish and irresponsible.

Nevertheless, Pig was honored with one of Hollywood’s highest distinctions: a nomination for Best Documentary Feature. Characteristically, de Antonio did not think much of the Academy Awards and its self-congratulatory pageantry. Writing to co-producer Moxie Schell, he pondered, “I’m sure we won’t win but it is odd, isn’t it? The picture, I suspect is too good for it. Most of the pictures which have won in this category are about nothing…” Pig did not win the big prize, but in 1975, a documentary about Vietnam did take home the golden trophy: Peter Davis’s Hearts and Minds. Davis’s film looked at the impact of the Vietnam War on individuals, like an American POW on a goodwill tour, a dissident serviceman who became part of the anti-war movement, and a Vietnamese villager. This deeply personal approach is very different from de Antonio’s political-historical film: it is arguably more of a document of postwar contrition than a searing analysis from the middle of the anti-war movement. De Antonio scorned Hearts and Minds, which was enough to start a spat with director Peter Davis, documented in the collection. Strangely enough, at the time, New Hollywood production company BBS was distributing both Hearts and Minds and de Antonio’s newest feature, Underground.