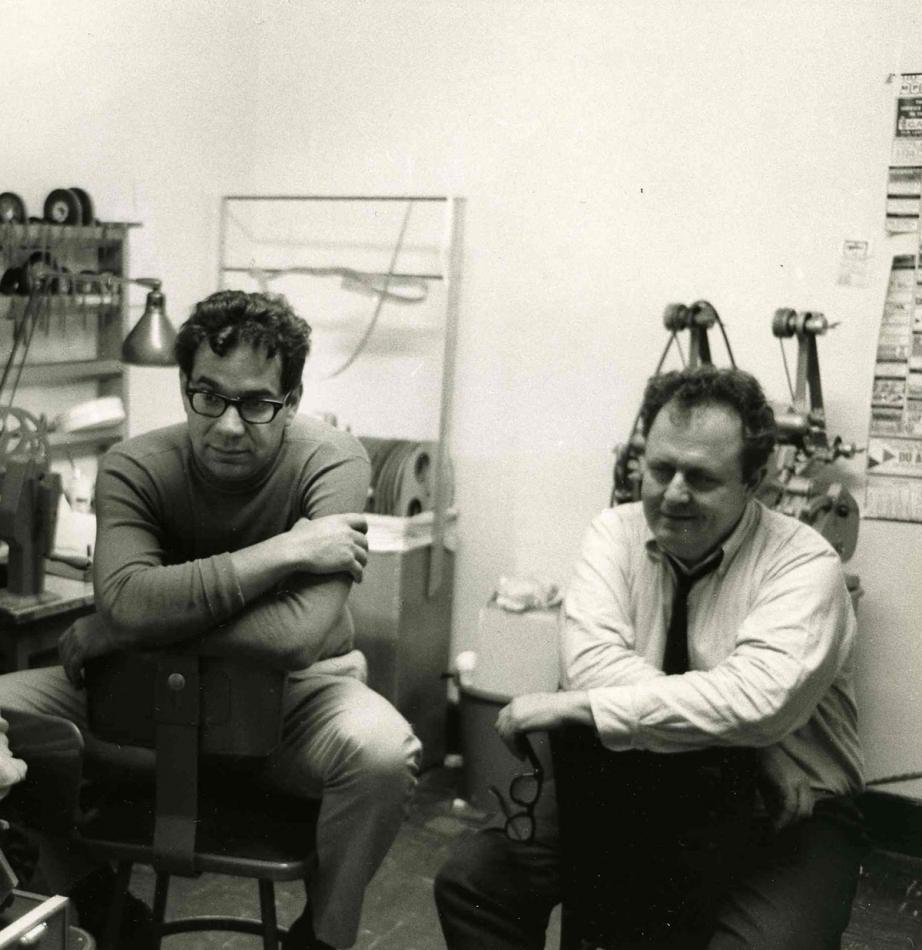

After the surprise success of Point of Order, de Antonio made a film that touches on one of the era’s most sensitive subjects: the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. De Antonio had been at Harvard at the same time as Kennedy, so he felt a distant personal connection to the president, as well as a patriotic feeling for the tragedy. Of course, de Antonio’s patriotism generally manifested in a distrust of the government, and this case was no exception: de Antonio partnered with author and political gadfly Mark Lane, an outspoken critic of the official “final word” on the assassination, the Warren Commission Report. Working together, they interviewed a number of assassination witnesses in Texas in the spring of 1966. Over the next few months, de Antonio and assistant Dan Drasin edited together the interviews to create an audiovisual brief for the defense of slain suspected assassin Lee Harvey Oswald.

After the surprise success of Point of Order, de Antonio made a film that touches on one of the era’s most sensitive subjects: the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. De Antonio had been at Harvard at the same time as Kennedy, so he felt a distant personal connection to the president, as well as a patriotic feeling for the tragedy. Of course, de Antonio’s patriotism generally manifested in a distrust of the government, and this case was no exception: de Antonio partnered with author and political gadfly Mark Lane, an outspoken critic of the official “final word” on the assassination, the Warren Commission Report. Working together, they interviewed a number of assassination witnesses in Texas in the spring of 1966. Over the next few months, de Antonio and assistant Dan Drasin edited together the interviews to create an audiovisual brief for the defense of slain suspected assassin Lee Harvey Oswald.

Filmed in black and white, the film shows Lane soberly introducing photographic evidence and interviewing witnesses who contradict the Warren Report. Its spare style underlines the seriousness of the subject and betrays none of the conspiracy theory histrionics that one often associates with counter-histories of the assassination. Though the topic was controversial and current, de Antonio predicted that the “art brut” style would turn off audiences.

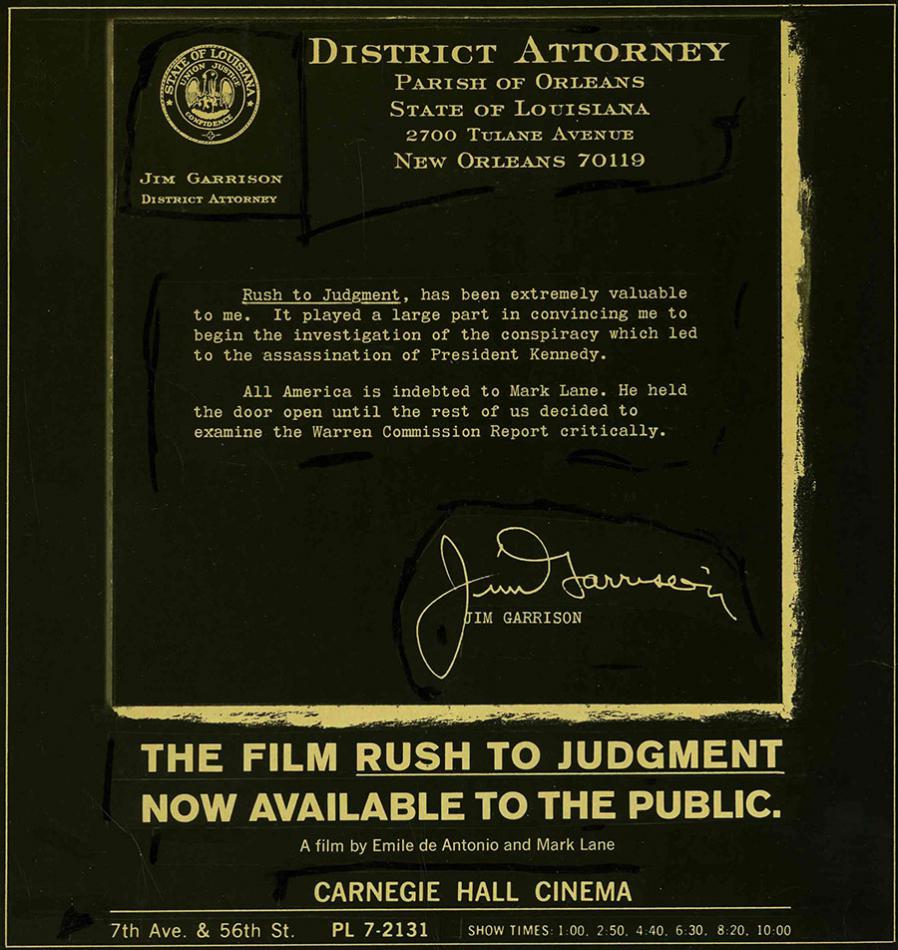

Nevertheless, Mark Lane’s rising star, and the public’s increasing skepticism about the Warren Commission Report’s findings seemed to guarantee the film’s commercial prospects. In August 1966, Lane published a book, also entitled Rush to Judgment. It quickly attracted a great deal of attention and climbed the bestseller list. Lane promoted his book incessantly through lectures and a regular guest spot on Mort Sahl’s radio show. However, Lane’s high profile did not convince any powerful distributors to take on the film. The collection contains numerous letters of rejection from established distribution companies in the United States and abroad. De Antonio was convinced that the American government, possibly the FBI, was applying political pressure that led to these rejections, a notion he kept up when exhibitors declined to show Rush to Judgment. However, the collection points to a number of factors, besides political censorship, contributing to the film’s commercial failure.

While de Antonio tried to find a film distributor, an arduous process documented in correspondence, Impact Films agreed to distribute Rush to Judgment as a last resort. Headed by Lionel Rogosin and Max Osen, Impact Films was a newly-formed distribution company that soon ran into internal problems, which likely hampered its ability to secure exhibitors for Rush to Judgment. Their job was made more difficult by the film’s airing on British television. Though the filmmakers gained a hefty fee of $30,000 for the single showing on the BBC, the film was butchered in its transmission, with crucial shots removed and interruptions for “debate” between Lane and four inquisitors who roundly dismissed the film’s argument. Cables and letters document de Antonio’s insistence that the film not be cut, and his irritation at the matter being out of his control.

Rush to Judgment’s movement through the market demonstrates the pitfalls of partnerships in filmmaking, as well as the difficulty in distributing independently-made films. In spite of these pitfalls, de Antonio continued to make independent films for two more decades, experimenting with both film form and ways of getting his films to audiences.