Click here to view all photos

When the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research acquired the United Artists papers in 1960, publicity still keybooks were among the materials it acquired. Because of their unbroken chain of provenance, the United Artists constitute a separate collection, known as UA Series 5.6. These files are remarkable records of on-set still photography in the classical Hollywood era. With more than 400 stills, the Foreign Correspondent file is particularly detailed. It documents not only the production’s complex special effects and massive sets, but also the promotion of the film’s stars (and its star director).

Foreign Correspondent was loosely adapted from the memoir Personal History by well-known foreign correspondent Vincent Sheean. Producer Walter Wanger, who joined United Artists in 1936, held the rights to the book. Personal History was a pet project of Wanger’s, who began pre-production in 1938. For his director, Wanger selected Alfred Hitchcock who had recently come over from Britain and was on contract with independent producer David O. Selznick. But Selznick’s excessive oversight over the direction of Rebecca (the British director’s first American project) displeased Hitchcock, and he jumped at the chance to work at United Artists for his regular weeky salary of $2,500 (though Wanger paid Selznick $7,500 for the loan).

As a matter of taste, Hitchcock far preferred “thrillers” like Foreign Correspondent, and once remarked of the more critically acclaimed Rebecca, “Well, it’s not a Hitchcock picture; it’s a novelette, really.” When both pictures were nominated for the Academy Award that year, Rebecca won; Foreign Correspondent did not garner the Oscar win in any of its other five nomination categories.

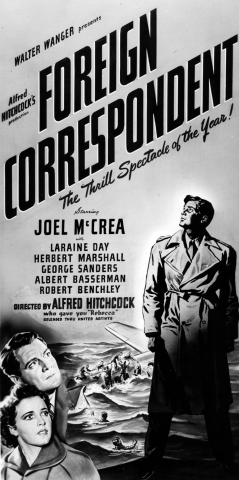

Unlike Selznick, Wanger allowed Hitchcock a great deal of latitude and did not interfere, even when Hitchcock’s shoot went over budget. Wagner did, however, object when he learned that the bad guys were slated to speak German. As a compromise, the dialogue was rewritten into a “nonsense” language—German backwards. Even so, the anti-German script sparked controversy almost immediately: Bank of America announced that it would not fund any Wanger projects if the project was completed. Nevertheless, Wanger continued to pay writers to work on the adaptation of Personal History. When England declared war on Germany on September 3, 1939, Wanger, who had already sunk $140,000 into writing costs, saw his opportunity. He announced that the adaptation of Personal History would go into full-scale production in November of 1939, and began to place advertisements for the picture in the trades, touting Charles Boyer and Claudette Colbert as the romantic leads. Ulitmately, he got neither. Joel McCrea and Laraine Day starred instead.

Hitchcock theorized that bigger stars would translate into bigger suspense in audiences, a principle he often credited as the basis for his decision to move to Hollywood (though the war seems a more likely candidate). He wanted Gary Cooper and Barbara Stanwyck for the lead roles. Cooper, however, turned up his nose at the idea of working on so low a genre as the thriller, and Stanwyck was otherwise occupied. It seemed big stars had little interest in big suspense. For the rest of his career, Hitchcock would complain about McCrea, saying he had to “make do” with the “too easy-going” male star. Hitchcock also reportedly bemoaned the fact that he couldn’t get a “bigger name” than Laraine Day. However, Foreign Correspondent proved to be a major break for her.

Hitchcock was pleased, however, with the supporting players. He asked Robert Benchley, a humorist for the The New Yorker and a comedy writer as well as an actor, to write his own dialog. It included the declaration that Benchley’s character hated milk, for which the Creamery Buttermakers Association filed a complaint with the MPPDA. The cast also featured George Sanders and Herbert Marshall.

Alexander Golitzen and his associate Richard Irvine are credited with the art direction, which included reproductions of Waterloo Station, the Hotel Europe, two luxury liners, one clipper plane, and a three-story windmill. A total of seventy-eight sets were constructed on five stages on the United Artists lot, but the grandest by far was the Amsterdam square, which showcased a state of the art rain effects system. Hitchcock also added several scenes to the script, including the windmill scene, the plane crash, the elopement-kidnapping, and the assassination of the ambassadorial impersonator.

European location shooting was done by British cinematographer Osmond Borradaile, who was forced to reshoot everything when his trans-Atlantic liner was torpedoed by a U-boat. All of Borradaile’s film and equipment was lost, though he survived. William Cameron Menzies was charged with special production effects. He teamed with special effects photographer Pau l Eagler (who had pioneered matte photography in 1916) to design the clipper sequence. The two made elaborate story-boards.

According to American Cinematographer, the climactic plan crash depicted in the film was achieved in this way: “Visual effects director Eagler photographed a pilot’s scale POV scene of an aircraft plunging toward the ocean. The daredevil pilot, Paul Mantz, pulled the plane out of the dive at the last practical instant. The scene was projected onto a process screen made from rice paper and installed outside the windshield. In the foreground were the stunt men portraying the flight crew; behind the screen was a large water tank. As the aircraft neared the surface of the ocean in the projection, the direct or pushed a button to release a flood of water which obliterated the screen as it burst into the cockpit and swamped the stuntmen. Filmed without a cut, the effect is absolutely convincing.” Production records indicate that the plane crash effect added $250,000 to the film’s budget. The aircraft was a full-scale mock-up of an Imperial Airways Empire Flying Boat, made at the cost of $47,000. The water tank used for the crash sequence was also featured in Samuel Goldwyn’s production, The Hurricane. Tank shooting lasted a total of nine days.

Writer Ben Hecht, known for his skill as a script doctor, was brought in for the final scene. His dialog emphasized the crisis brewing in London: “I can’t read the rest of this speech I have because the lights have gone out…” Roughly a month after shooting wrapped, the Axis powers were officially established when the Tripartite Pact was signed by Germany, Italy, and Japan on September 27, 1940. The film was released fourteen months before the U.S. entered World War II. Foreign Correspondent’s costs totaled $1,484,167, making it by far Wanger’s most expensive production. Even so, and in spite of the closed markets abroad, it earned $369,973 in profits in 1940.