While Altman left television in the mid 1960s for feature film production, his first full-blown success did not arrive until M*A*S*H, released in 1970 to critical raves and boffo box office. This success catapulted Altman into a decade of intense productivity, and the WCFTR’s Robert Altman Papers, while covering only 1969-1972, contain files on five films. The holdings for each of these works illuminate characteristic aspects of Altman’s directorial stamp and demonstrate how he positioned himself within a new wave of American auteurs.

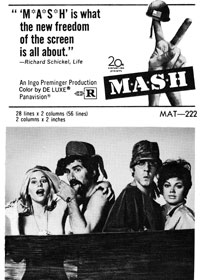

M*A*S*H

Not only was Altman, famously, the fifteenth director Ingo Preminger approached to helm M*A*S*H, he was also provided with a script by the highly regarded screenwriter Ring Lardner, Jr. for the film. Despite these facts, Altman attempted to make M*A*S*H his own and was resentful when Lardner received sole credit for the screenplay and failed to acknowledge Altman’s contributions when he was awarded the Oscar for his work on the film. The film’s file in the Altman collection contains both the final version of the script as well as the scene-by-scene breakdown Altman used for shooting it.

The file also illuminates some of the filmmaker’s negotiations with the Motion Picture Association of America’s Code and Rating Administration. Warned that the film would receive an X-rating unacceptable to the film’s distributor, Twentieth Century Fox, Altman and Preminger were forced to meet with the studio’s legal department and representatives of the Rating Administration to discuss changes to its script. The Altman collection includes both the letters (from Ferguson and from Dougherty) that sparked the forced consultation and the notes from the meeting itself.

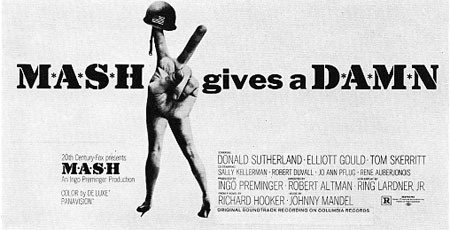

These materials shed light on what was perceived to be the greater range of freedom accorded to filmmakers in the late 60s and early 70s and on how that freedom was managed and negotiated. While the Ratings Administration’s list [MASH5, 6, 7] of specific problem areas in the film’s script include every use of the word “damn” the filmmakers would go on to sell the film through the tagline “M*A*S*H gives a D*A*M*N” (seen above). After looking over the documents, it may be enlightening to examine the film and see how many changes and how much of Altman’s promised restraint are reflected in the final product.

The final component of the M*A*S*H file is a set of short papers a film professor at UCLA asked his students to write after a special screening of the film. The papers reveal that with M*A*S*H came the beginnings of Altman’s acceptance as a serious film artist, someone whose work needed to be taken seriously by academics and hopeful film critics.

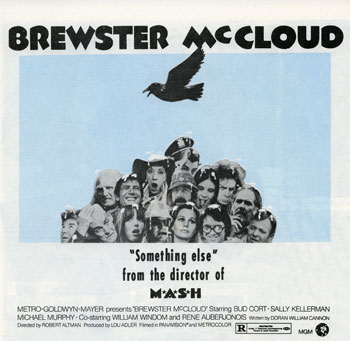

Brewster McCloud

Altman’s first film after his breakout success is also the least seen of his features from the early 1970s. The Brewster McCloud file in the Altman collection includes its production schedule and daily production reports, but the WCFTR holding that best captures the film’s place in Altman’s career is its press book, which can be found among the WCFTR’s Photos and Promotional Materials. The film’s publicity promises “Something else” from the director of M*A*S*H, highlighting Altman’s authorship as a selling point. Altman’s photo is even included as one of the headshots on the film’s poster.

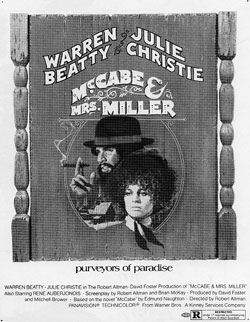

McCabe & Mrs. Miller

The Altman collection’s file on this revisionist western documents many of what would come to be understood as Altman’s authorial hallmarks. Altman was known for having his actors improvise their scenes on set, often asking them to create or alter their own dialogue before filming. The file includes the first draft of the script by Brian McKay, originally titled “The Presbyterian Church Wager,” which can be compared to the shooting script and its breakdown, also included in the file. This shooting script [IV-6] can then be compared to the final film to provide one example of Altman’s approach to the script in his films.

The scene breakdown for filming consists of a shot-by-shot breakdown of the scene to be filmed, along with details about camera lenses and movements. Each breakdown faces the script page that is to be shot. This provides the researcher with a means of reconstructing the stylistic decisions made by Altman and his cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond. One example from the breakdown [IV-5], which describes scene 40, provides a useful example. Several of what would become recognized as Altman’s stylistic signatures are evident in the breakdown, including his use of a “pan and zoom” style, on display in 40 and 40A, and his use of telephoto lenses, as evidenced in 40B.

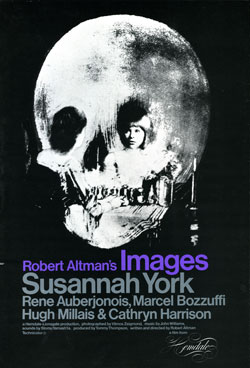

Images

Images is the Altman film whose fragmented narrative and emphasis on ambiguous visual motifs most resembles the work of European art cinema auteurs like Bergman and Fellini. It is also the only one of his films from the early 1970s for which he is sole author: Altman originated the idea for the script and wrote it himself. The Images file documents the filmmaker’s work through eight drafts of the screenplay, including a first draft with handwritten notes scrawled on a yellow legal pad. The file also includes a press packet assembled for the film’s French promotion. The packet attempts to position the film as the visionary work of a distinct auteur. One passage specifically addresses the problem of situating Images within the Altman oeuvre.

On the surface, fans of Altman will find Images immeasurably different from M*A*S*H, Brewster McCloud, or McCabe & Mrs. Miller—that is to say, as alien as even those films appear to one another. But as nine tenths of an iceberg rests beneath the surface, so, too, does an Altman film; and the observant may see or feel a pattern, a particular angle of vision, that ties these works together.

Images‘ promotional material argues that what would seem to be most resistant to claims for Altman’s auteur status—the lack of unity in his filmmaking—is actually what positions him as the ideal object of serious critical study. Its call for a search for patterns easily overlooked by the average observer was, perhaps, veritable catnip for film scholars and journalists.

The Long Goodbye

Finally, the WCFTR’s Altman Papers include extensive documentation of the production of this loose adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s novel. Daily production reports, production schedules, and camera tests, as well as the contact proofs included in the WCFTR’s collection of Photos and Promotional Materials, provide the film scholar with an intimate view of Altman’s filmmaking practices.

Patrick McGilligan’s interview with Elliot Gould also grants insight into Altman’s working methods.

Gould’s description of the shooting of a hospital scene that takes place late in the film provides a window on Altman’s collaboration with actors he respects. Gould’s description can be compared with the scene as described in the WCFTR’s copy of the revised version of the script by Leigh Brackett, who also adapted Chandler for the Howard Hawks’ 1946 film, The Big Sleep.

Digital Documents