When the quality of Altman’s independent production, The Delinquents, landed him a directing job at Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Altman embarked upon a decade of work in television. He would direct over a hundred episodes for more than twenty different series, many of them rarely seen and unavailable on home video. Altman’s television legacy presents an open question for Altman scholars. What is the relationship between his work as a director for hire and his string of critical successes in the 1970s? To what extent did the conditions of directing series television constrain or enable his development as a filmmaker? Historians of film aesthetics must tread particularly carefully when assessing authorship in television, which is traditionally understood as a producer’s, rather than director’s, medium.

Troubleshooters

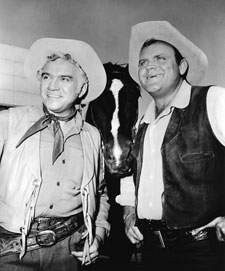

The WCFTR’s United Artists collection sheds some light on Altman’s work on at least one of the many series with which he was involved, the United Artists show, Troubleshooters. The series, which premiered on September 11, 1959 on NBC, might best be described as an engineering adventure show. In it, the crew of the San Francisco-based Stenrud Construction Company travels around the world, completing major projects despite frequent novel and unlikely obstacles. Filmed entirely in Southern California, the show starred character actor Keenan Wynn as the crew’s “top push,” Kodiak, and gold medal winning Olympic decathlete Bob Mathias as his engineer and right hand man, Frank Dugan. The show debuted in a particularly difficult slot, facing off against the popular Western Rawhide on CBS and Walt Disney Presents on ABC. Sponsored by Marlboro cigarettes, the series prominently featured Caterpillar construction and excavation equipment, provided in a mutually beneficial arrangement likely orchestrated by Altman, who had made several sponsored films, including A Perfect Crime, for the company while at Calvin. In their annual report to shareholders, UA described the series as being “produced under the same policies which the parent company has applied successfully to independent motion picture production.”

According to a Los Angeles Times article published the week of the premiere, the idea for the show originated with Wynn, who believed a television program would serve as the perfect vehicle for his character actor-plus qualities. Motion picture producers, he complained, were increasingly unwilling to pay what he felt was a fair value price for his services. McGilligan writes that both Altman and producer-screenwriter Allen Rivkin were brought on board at Wynn’s request. Rivkin and Altman developed and cast the show together, but McGilligan writes that the two were frequently at odds: indeed, Rivkin described the experience as “one of the worst of his life.”

According to McGilligan, “Altman changed dialogue and scenes and was filming straightaway without the producer’s approval. The pace was so relentless—two episodes a week—and the budget so minimal that after a time Rivkin threw up his hands. No matter what he did, Altman would be out in the hills somewhere, simulating some exotic locale, and doing exactly what he liked.” Altman himself claims that during his early television days he worked so fast that his crew would often finish early and rather than starting on the next episode, “the trick was to stay out almost all day, so we started doing reflection shots and all kinds of complicated stuff just to fill the day out.”

Troubleshooters, then, provides a glimpse of Altman unleashed (or at least Altman with a considerably longer leash than was the norm on television). Fortunately for the Altman scholar, then, the WCFTR’s Troubleshooters-related holdings include 16mm prints of all twenty-six episodes of the series, as well as production stills and dialogue continuities, and some sparse records of the show’s conception and development.

The episodes of Troubleshooters directed by Altman provide evidence of a distinct approach to television direction that presents continuities with both his earlier approach at Calvin and his later approach to feature filmmaking in the early 1970s. Altman often noted that he used his television assignments to direct mini-movies, small-scale versions of popular films or European films that he admired. This is a tendency that is clearly on display in Troubleshooters, with episodes that emulate or pay homage to Henri-Georges Clouzot’s The Wages of Fear, Vittorio De Sica’s Italian neorealist classic, The Bicycle Thief, and Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole. One of Altman’s episodes even owes its name to the Jean Renoir film, The Lower Depths, although its subject matter deals with decompression chambers required for deep sea drilling rather than poverty and social despair.

Altman’s episodes both set the basic stylistic parameters for the series and demonstrated virtuosic flourishes that serve as a hallmark of his television work. While the series’ low budget constricted the potential complexity of its lighting and camera movement, Altman found ways to experiment, much as he did at Calvin, within stylistic boundaries and technological limitations. The show’s style tended towards greater depth staging and more distant framings than one might expect from television, stereotypically described as dependent on close-ups and medium shots. These traits can be attributed, in part, to the series’ large-scale subject matter, but Altman also created comparatively elaborate set-ups that took advantage of the premise’s stylistic demands to test what he could accomplish.

One such experiment takes place in a long take during an episode titled “The Cat-Skinner.” Kodiak sits at a picnic table under an umbrella in a longshot in the distant foreground screen right. A Caterpillar bulldozer drives across the screen in the middleground and then Dugan’s jeep drives towards the camera from the distant background. The camera pans left to follow the jeep as it arrives in the foreground and then right as Dugan exits the jeep and takes a stance in a medium shot in the foreground. Kodiak then walks from his seat at the table into the foreground next to Dugan. After two close ups of the actors, Altman cuts back to the previous set up and the camera pans left as Dugan gets into his jeep, and then right as he goes back down the road, with Kodiak remaining in the foreground.

Such a shot might not stand out as particularly expressive given the norms of Hollywood feature filmmaking or European art cinema, but it does stand out given the norms of television and the Troubleshooters series. Other episodes featured experimentation of different kinds, including the overlapping dialogue that would become an Altman trademark, and a journey into the mental subjectivity of a disturbed World War II Japanese officer who refuses to admit defeat and surrender his remote island to the team of construction workers and engineers who discover his base.

Finally, Altman’s work on Troubleshooters displayed a tendency that would continue throughout his filmmaking career of establishing and maintaining an extended coterie of actors. This is certainly a central feature of series television production in general, but, as with the series’ style, Altman elaborates this basic trait. Whereas most Troubleshooters episodes not directed by Altman focus on the Keenan Wynn and Bob Mathias characters almost exclusively, the majority of Altman’s episodes also provide roles for a supporting cast made up of Altman’s friends and discoveries, people with whom Altman felt it would be fun to work. This extended cast included four other construction workers, each with a distinct characteristic: Jim (Bob Harris) is the strongman, Scottie (Forrest Compton) is the rough ladies’ man, and Skinner (Carey Loftin) is older, more experienced. The final member of the quartet is Slats, the beanpole, and is played by Chet Allen, the production designer of Altman’s The Model’s Handbook. Other directors of Troubleshooters seemed incapable of finding much use for these characters, but they consistently play a role in the Altman episodes, creating an atmosphere reminiscent of the brotherhoods of competent professionals found in so many of the films of Howard Hawks, who was likely a significant influence on Altman.

Bonanza

Altman’s work on Bonanza later in his television career was less freewheeling than that on Troubleshooters. The series’ creator and producer, David Dortort, had firm control over the show’s production. This is not to say, however, that Altman’s direction on the show was anonymous. In an interview with McGilligan, Dortort discusses what made Altman’s contributions distinct (audio will open in new window), and offers an analysis of his series’ directors that is of great interest to scholars of television and authorship.

The WCFTR’s collection of David Dortort’s papers also provides vital documentation of the episodes Altman directed for the series, including daily production reports and shooting scripts for every episode.

Digital Documents