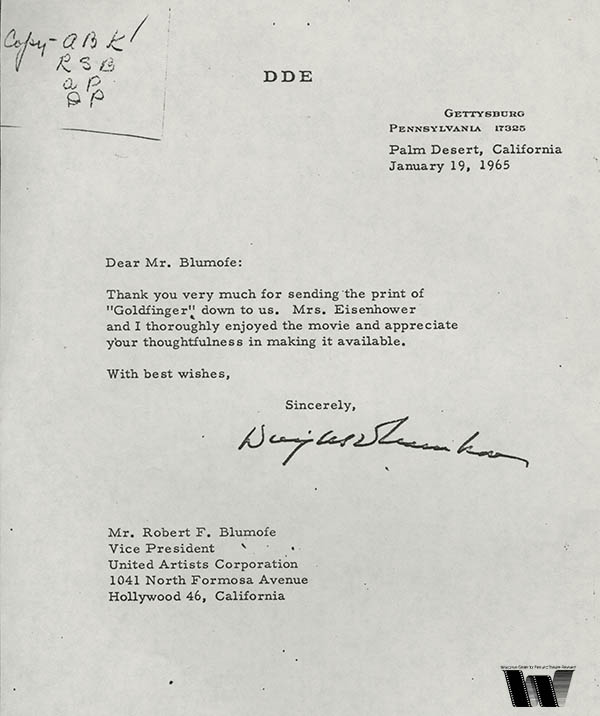

A modest abbreviation, “DDE,” sits at the top of the page. Note the “no-nonsense” quality of the text: a simple thank you note to Robert M. Blumofe, the Vice President of United Artists, for arranging the shipment of a 35mm print of Goldfinger to Palm Desert, California. The person who actually wrote the letter is likely anonymous, an unidentified assistant tasked with keeping up on professional correspondence. But the signatory at the bottom of the letter is not. All of it befits the style of a humble ruffian from Abilene, Kansas who would rise to greatness as the 34th president of the United States: Dwight David Eisenhower. (the letter can be found in UA MCHC 82-046 Box 3 Folder 11)

A modest abbreviation, “DDE,” sits at the top of the page. Note the “no-nonsense” quality of the text: a simple thank you note to Robert M. Blumofe, the Vice President of United Artists, for arranging the shipment of a 35mm print of Goldfinger to Palm Desert, California. The person who actually wrote the letter is likely anonymous, an unidentified assistant tasked with keeping up on professional correspondence. But the signatory at the bottom of the letter is not. All of it befits the style of a humble ruffian from Abilene, Kansas who would rise to greatness as the 34th president of the United States: Dwight David Eisenhower. (the letter can be found in UA MCHC 82-046 Box 3 Folder 11)

As many presidential historians would tell you, the one most strongly associated with James Bond was Eisenhower’s successor, John F. Kennedy. In 1955, Kennedy read the first James Bond novel, Casino Royale, while recuperating from a back injury. He continued to read other books in the series and later named From Russia With Love as one of his ten favorite books.

During Kennedy’s presidential campaign, a mutual friend introduced the candidate to the author of the Bond series: “Mr. Ian Fleming-Senator Kennedy.” Fleming attended a party later that day hosted by the Kennedys. When the Senator asked Fleming how he would depose Cuban leader, Fidel Castro, the Bond author proposed dropping pamphlets on the island that claimed that beards attracted radioactivity, a scheme designed to get Castro to shave off his most distinctive feature.

Kennedy’s interest in Bond continued throughout his presidency, albeit in more private fashion. From Russia With Love (1963) is reportedly the last film that Kennedy screened at the White House before his fateful trip to Dallas. Even more bizarrely, it is alleged that both Kennedy and his assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald were reading James Bond books the night before the latter shot the former in Dealey Plaza on November 22, 1963.

Sadly, Kennedy would not live long enough to see the release of Goldfinger. But Eisenhower would and did!

Goldfinger had its U.S. premiere in New York on December 21, 1964. It would open in Hollywood just days later on Christmas. Considering the date on Eisenhower’s “thank you” note – January 19, 1965 – it appears that United Artists’ brass made special arrangements for the former president to screen the film with his wife, Mamie. At a time when UA had prints circulating in key cities like Cincinnati, San Francisco, Denver, Chicago, Seattle, and Washington D.C., they sent a print to Eisenhower’s vacation home in Palm Desert, a town with approximately 1300 residents in 1965.

Yet such is the power of the presidency. Although Eisenhower was not a self-identified fan in the way Kennedy had been, he reports that he and Mrs. Eisenhower – ever the politician –“thoroughly enjoyed the movie.” Of course, none of this would be a surprise to Ian Fleming. As the author told Playboy magazine just before Goldfinger’s release:

…many politicians seem to like my books. I think perhaps because politicians like solutions, with everything properly tied up in the end. Politicians always hope for neat solutions, but so rarely can they find them.

Perhaps the even bigger irony in all of this is the fact that both Eisenhower and Kennedy helped create the geopolitical conditions that would make James Bond a popular character in the first place. Under Eisenhower’s leadership, CIA director Allen Dulles orchestrated successful coups in Iran and Guatemala. Dulles also oversaw the failed Bay of Pigs invasion three months after Kennedy was inaugurated.

Allen’s older brother, John Foster Dulles, also became a key architect of America’s Cold War policy as Eisenhower’s Secretary of State. John Foster Dulles would strengthen the U.S. role in NATO and create the Southeast Asian Treaty Organization as bulwarks against Communist aggression. Containment policy lent organizations like the CIA and MI6 a significance that they otherwise would have lacked. It also endowed Ian Fleming’s stories with a topicality and resonance that would prove important to their popularity long after the author had shuffled off his mortal coil. When Dr. No was released in October of 1962, just eleven days prior to the Cuban missile crisis, the idea of a madman creating his own nuclear weapons on a small island just off the U.S. seemed like it was ripped from the day’s headlines.

Of course, Bond’s popularity extended well beyond the Cold War period. The greatest action hero the world has ever known, Bond would go on to fight drug dealers in Live and Let Die (1973) and Licence to Kill (1989), a Silicon Valley millionaire in A View to a Kill (1985), oil magnates in The World is Not Enough (1999), a cyberattacker in Skyfall (2012), and even a high stakes poker player in the reboot of Casino Royale (2006). Eisenhower’s “thank you” letter to UA provides insight to James Bond’s enormous popularity at an early stage of the character’s cinematic history. It also shows how a former Commander in Chief could commandeer a Commander from Britain’s Royal Naval Reserve.

— Jeff Smith is the Director of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research and a Professor in the Department of Communication Arts. His first book, The Sounds of Commerce: Marketing Popular Film Music, features a chapter on the soundtrack for Goldfinger.