The KFIrings

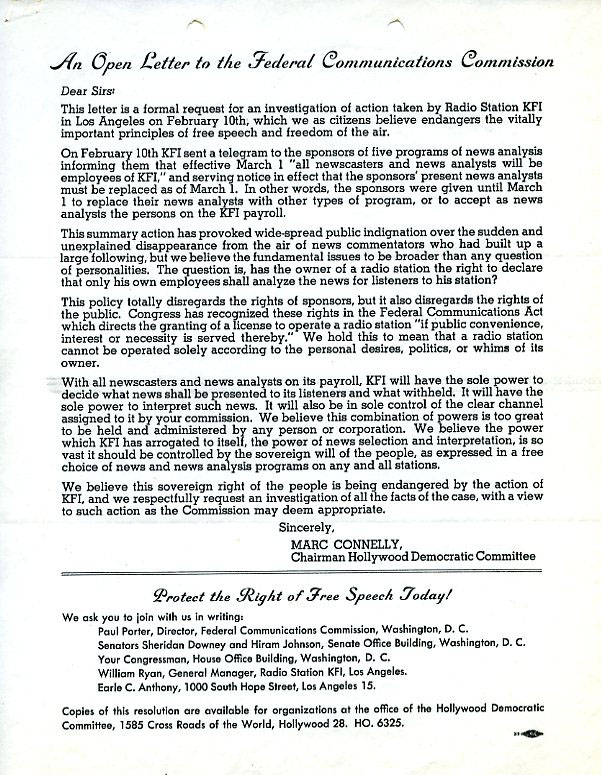

One of HDC’s first major fights against censorship came in 1945 when KFI Los Angeles, one of the biggest stations in the country, fired its sponsors’ popular news analysts and replaced them with in-house employees of KFI. While radio or television stations commonly employ in-house news anchors today, earlier periods of radio saw sponsors responsible for much on-air content; sponsors designed programs they wanted to associate with their products while stations and their owners provided airtime. Sponsors and the public saw KFI’s move to feature only handpicked news analysts as an attempt to control speech over the airwaves. In an open letter to the FCC, Marc Connelly, then HDC Chairman, wrote, “This policy totally disregards the rights of sponsors, but it also disregards the rights of the public…With all newscasters and news analysts on its payroll, KFI will have the sole power to decide what news shall be presented to its listeners and what withheld. It will have the sole power to interpret such news.” As evidence of the attempt to abridge speech, many cited the possible motivations of wealthy station owner Earl C. Anthony, a major donor to anti-labor and anti-administration activities, and the political leanings of the fired analysts, three of whom were among the most progressive voices on American airwaves. Given KFI’s location and size, the anti-administration, anti-progressive nature of the firings, and the dangerous precedent the move might set for ownership and control over broadcast communication and the arts, the HDC was particularly invested in the outcome of the dismissals. Consequently, the HDC began a campaign to revoke KFI’s broadcasting license and turn public sentiment against the station’s leadership.

A key weapon in the HDC’s arsenal against KFI was the Federal Communications Act of 1934. Borrowing language from the Radio Act of 1927, the 1934 legislation declared the airwaves a public resource and subsequently hinged broadcast licenses and renewals on a station’s ability to meet “public interest, convenience, and necessity” (also known as PICAN standards). Much of the HDC’s correspondence concerning the KFI dismissals directly quote or otherwise allude to PICAN standards and call for immediate FCC action, arguing that the firings work against the public interest by diminishing choice and the free flow of information. This tactic, however, would prove ultimately unsuccessful.

Regulatory Trouble

The first challenge presented by a campaign against KFI was the vague language of the Communications Act. The legal meaning of “public interest” was not clearly defined within the legislation, making it a point of struggle between various parties—in this case the HDC, legislators, FCC employees, and the station owner—who all attempted to shape the words’ meaning to suit their own needs and interests. However, even if the HDC could successfully defend its own definition of “public interest,” forcing regulators to act immediately would present another problem. Since the Communication Act regulated only station license grants and renewals, there was little the regulatory body could do before the expiration of KFI’s current license, which extended for another full year. A letter (signed by “Ruth”) from Ellis E. Patterson’s office illustrates yet another difficulty inherent in enforcement through the FCC: any investigative action in congress—the first step to beginning an FCC inquiry—would require the appointment of a committee whose membership and political leanings could not be predicted. Instead of working with the FCC, Ruth suggested using public sentiment alone to fight the dismissals, since public pressure could offer a quicker and surer solution. Furthermore, if the initial campaign was unsuccessful, letters written directly to the station from listeners could weigh in the FCC’s decision on KFI’s license renewal. Implicitly admitting the weakness of regulatory standards, Ruth argues, “Knock them out in the first round, cause they’d love a long, slow battle to show them in the right, by law, which would set a terrible precedent.”

For its part, the FCC defended its inaction by invoking its own recent ruling in the Mayflower Broadcasting Corporation case—a precursor to the Fairness Doctrine—wherein the commission forbade stations to air news programs that editorialized or advocated particular issues or political stances, which they saw as contrary to serving the public interest. In letters to the HDC and its supporters in congress, the FCC argued that any violation of the Mayflower decision would result in a refusal to renew KFI’s license, implicitly suggesting that the regulatory measures already in place were an adequate tool for dealing with the station’s actions. As a side effect of the FCC’s reliance on the Mayflower decision, which defined unfair speech as blatant editorializing rather than the intentional silencing of particular viewpoints, the FCC effectively put an increased burden of proof on those protesting the type of actions taken by KFI.

Aftermath

In 1946, when KFI’s license expired, the FCC only granted the station a temporary renewal license while it undertook investigations of the firings. The victory was short-lived, however, since KFI ultimately received a full license the following year. A report of the 1947 FCC decision notes that only one member of the commission, “lone wolf” civil rights and New Deal advocate Clifford J. Durr, dissented from the renewal. Calling for a public hearing, Durr echoed the HDC’s and others’ arguments regarding the threat of censorship, noting, “The complaints against station KFI got to issues which are fundamental to the operation of a broadcasting station in the public interest—namely, fairness and balance in the presentation of news and opinion.”

Like many of the other materials pertaining to HDC’s organizational activities, the KFI collection offers a productive pivot point from which to explore other issues. Records reveal close working relationships between HDC members and congresspeople and offer insight into professional organizations working on political issues that touch their employment interests. The HDC’s records also reveal a complex struggle over the meaning of “public interest” and the value of regulation as different groups attempt to secure their interests through the FCC regulatory system. These same materials can also offer insight into failure. They describe a civic organization’s unsuccessful campaigns to navigate regulation and deploy public opinion and point to the weakness and ambiguity of communications regulation during the 1940s, when legislation intended to protect and promote speech enabled the silencing of particular voices.

Digital Documents:

Further Reading

Hilmes, Michele. Radio Voices: American Broadcasting, 1922-1952. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997.

McCauley, Michael P, Eric E. Peterson, B. Lee Artz, eds. Public broadcasting and the public interest. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 2003.

McChesney, Robert W. Telecommunications, Mass Media & Democracy: The Battle for Control of U.S. Broadcasting, 1928-1935. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.