In its early years, the Hollywood Democratic Committee operated primarily as an election organization. The group’s executive secretary and de facto historian, George Pepper, located the genesis of the HDC in loosely coordinated action among Hollywood figures in the successful 1938 election campaign for Democratic California Governor Culbert Olsen. It was shortly after Olsen’s loss to a Republican challenger in 1942 that the HDC formalized its organization in order to strengthen its ability to elect progressive officials.

Electing FDR to a Fourth Term

Though perhaps best known for its work on Franklin Roosevelt’s 1944 reelection campaign, the organization worked on local and state levels as well. Records of their work in 1943 and 1945 Los Angeles municipal elections reveal local elections to be a testing ground for election strategies like voter registration rallies and public film screening fundraisers. Questionnaires about candidates’ positions, correspondence, and platform materials indicate the extent to which the HDC saw local elections as key to carrying out the political aims they fought for in state and national elections.

The fertile training ground of the municipal elections lead to more developed strategies for the 1944 presidential and state campaigns. Although Roosevelt secured the Democratic nomination as the incumbent, several progressive California candidates for U.S. Congress and state government needed to beat challengers in the election primaries. Throughout the early part of 1944, the HDC focused its election efforts on supporting its local and state candidates, voter registration drives, and fundraising.

The Role of Radio

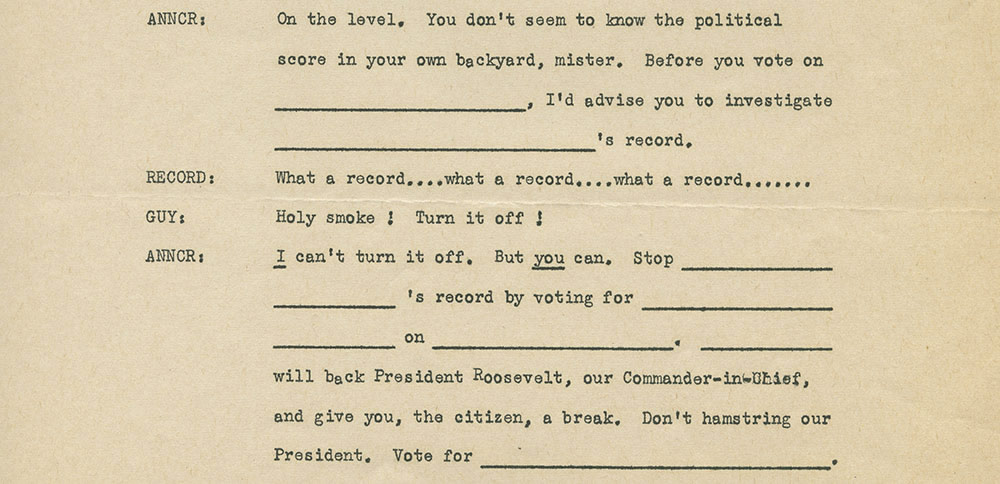

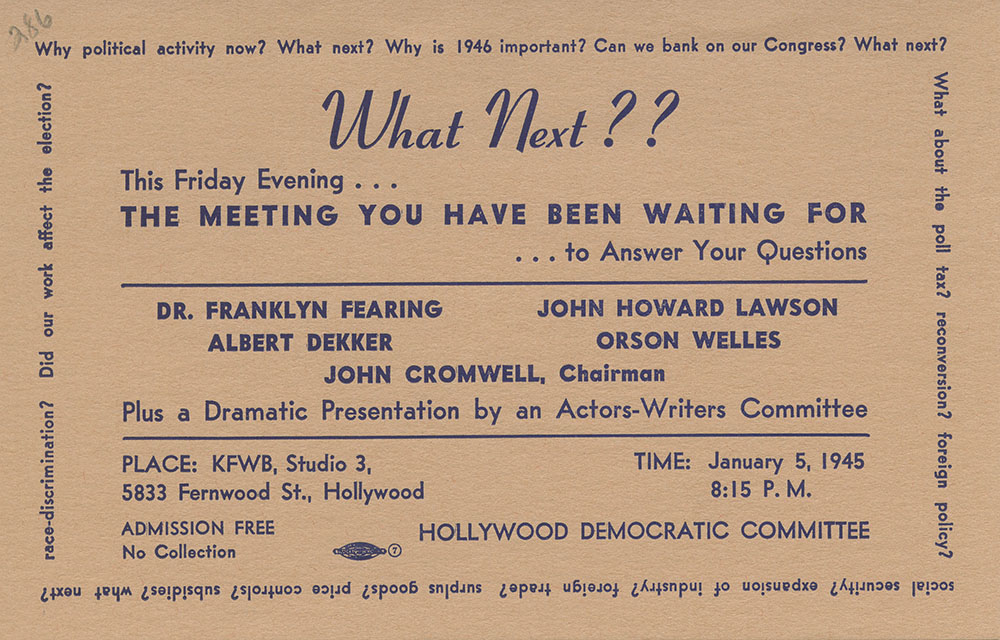

The HDC collection’s election scripts and recordings indicate the key role radio played in this strategy. One series of short spots explains the importance of registering by aligning soldiers’ efforts to win freedom for people in Germany and Japan with the freedom to vote. Pro-Roosevelt attack ads compare other legislators’ poor voting habits to a broken record and present their anti-administration votes as the behavior of a “gloomy gus.” Many of these scripts and recordings were also shared with the Democratic National Committee and tailored to races in other states. The HDC also tried to reach a national audience with star-studded radio broadcasts that discussed election issues through entertaining skits and songs. One such program, “Hollywood Town Meeting,” aired on CBS on May 11, days before the primary elections. Featuring stars Olivia De Havilland, Rita Hayworth, Gloria Stewart, and Rex Ingram discussing their viewpoints on issues such as isolationism, the poll-tax, and the Rooservelt administration, the show also featured political songs performed by Harry Stanton and Ida James.

After the primary vote on May 16, Thomas E. Dewey became the Republican nominee for president. Though the HDC campaign continued many of the same strategies used in the primaries and municipal elections, they also recalibrated to take advantage of the now-known identity of their challenger. Radio programs, such as “In Reference to Mr. Dewey,” attacked the candidate for his anti-progressive voting record and his affiliations with isolationists. The HDC’s show ont the eve of the election featured skits, speeches, and songs by Norman Corwin, Judy Garland, Humphrey Bogart, other stars, soldiers, and regular folk across the U.S. that similarly criticized Dewey while providing a laundry list of the Roosevelt administration’s accomplishments on jobs, the economy, fairer voting regulations, and public works projects.

Printed Campaign Materials

In addition to the radio programming of the 1944 primary and election campaigns, flyers, newspaper ads, and other printed materials also supported the president’s reelection bid. For the 1944 elections, the HDC created The Free Press, a political newspaper featuring stories, cartoons, and photographs covering vital election news. Some of their internal organizing efforts also doubled as publicity for Roosevelt. For example, a Hollywood Reporter ad announcing “Writers for Roosevelt” invited writers to bring their ideas “to a short, practical meeting to mobilize writing talent for the election campaign” and included a list of over one hundred writers supporting the administration.

Administrative Papers

In addition to radio scripts and publications, which often indicate only the end result of collaboration, some of the most revealing materials in the HDC election collections are the memos and meeting minutes that detail the HDC’s plan of action in the weeks leading up to election day. While many of the HDC’s campaign concerns ring true in today’s era of fundraising and canvassing, others—such as asking housewives to visit the homes of non-voters on election day and leaving them a stern note as a reminder of the polls’ closing time—may seem unusual. Furthermore, reports on issues such as improving worker efficiency, strategies to fight potentially corrupt election boards on election day, cooperating with other groups, and increasing voter turnout, reveal the ins-and-outs of an election campaign based not only on star-studded performances, but also on more mundane forms of organizing and civic participation.

Elections in 1946 and 1948

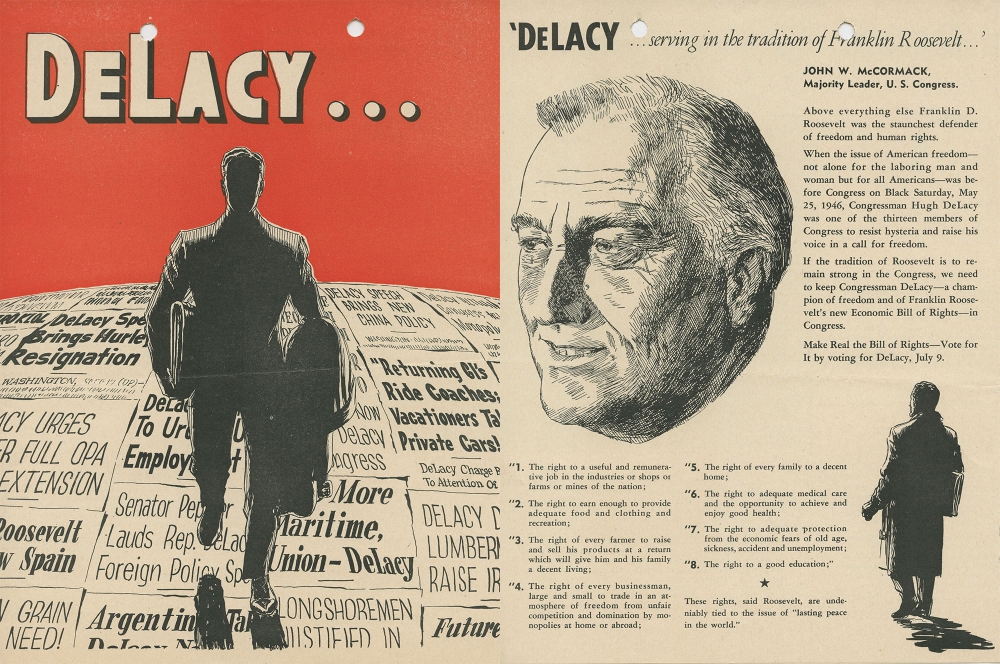

After the success of the 1944 presidential election, the HDC—then HICCASP—applied the strategies and lessons learned from the race to efforts in 1946 state gubernatorial and congressional elections. A report from the radio committee, for example, offers a snapshot of the organization’s evolving relationship with broadcast media. Though primarily devoted to describing radio practices employed in the 1946 elections, the report ends with a healthy list of observations and suggestions for the next election. These span changing narrative strategies, advertising policies, broadcasting areas covered, funding, and scheduling. Improbably, Roosevelt also maintained a central place in the election discourse. Rattled after the president’s death in 1945, HICCASP believed the 1946 elections were a key test of their ability to organize progressive political action without their longtime leader. Perhaps because of this, they kept Roosevelt and his legacy central in discussions of their candidates’ qualifications and political aims. Concerns about atomic energy, race relations, and anti-fascism became secondary, but equally important legislative issues for their efforts.

Records of campaign efforts thin out considerably for the 1948 elections. Comprised of a few radio scripts and flyers promoting third party Progressive presidential candidate Henry Wallace,t the collection bears little indication that H-ASP worked on state or local campaigns as they had in the past under the auspices of the HDC and HICCASP. What exists points to a similar dependence on radio for the campaign and an emphasis on Wallace’s support for cultural institutions. Of particular note are an election eve script bearing revisions marked by Wallace himself and a script for “Political Fashion Show,” a short satirical piece that translates the Truman administration’s policy decisions into “smart” sartorial choices. Roosevelt, under whom Wallace served as vice president from 1940 to 1944, again played a significant role in the language of the campaign. A twenty-two-page shot-by-shot film script that draws on Roosevelt’s legacy of criticizing the increased corporate control and militarization of government indicates that H-ASP may have expanded from radio to filmmaking in its later years.

Taken together, these election materials offer a look at political campaign strategy at midcentury. At the same time, they provide examples of an unusual form of Hollywood-based media production. While the lack of information in later files makes it difficult to know the extent to which H-ASP was involved in the Wallace campaign, this also points to the challenges of studying organizations and groups that don’t abruptly end as much as they slowly fade in power or relevance. This difficulty in locating precise ending dates for H-ASP’s political activities persists throughout the other branches of the collection.

Digital Documents

Further Reading

Boller, Paul F. Presidential Campaigns: From George Washington to George W. Bush. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Smith, Jean Edward. FDR. New York: Random House, 2007.

Yarnell, Allen. Democrats and Progressives: the 1948 presidential election as a test of postwar liberalism. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974.