The Rzhevsky collection includes diverse productions from across the Soviet Union. Just as the USSR tended to be Russocentric, so too was its film industry. Mos’film and Len’film were the two central fiction film studios responsible for the majority of the most well-known cinema across this period. Yet the Rzhevsky collection also includes some films from other republics interspersed among the productions from the Russian Republic. Before the war, cinematic portrayals of areas outside of Petersburg and Moscow tended towards viewing them as uncivilized backwaters the new Soviet project sought to modernize. Though output was scarce, most republics had been active in filmmaking since the beginning. Both Ukraine and Georgia had made films since the 1910s and had well-developed studios by the end of the war; both even had their own film schools in the post-war period. By then, all could be said to have mature film cultures to varying degrees. In fact, they made up a sizable portion of the Soviet film audience. As new theaters were built in more remote areas, box office attendance tended to pick up while it plateaued or dropped in urban areas with the rise of television. Because of their distance from the central administrative hubs of the industry, filmmakers working in this context often benefited from less oversight and looser censorship.

A mix of traditional genre fair and more personal projects were in the output of minor studios, just as was the case in the Russian Soviet. With some exceptions, Gos’kino would dub projects into Russian from the original language from the Republic, if it was felt that the film was of sufficient merit to distribute across the USSR. One such exception found in the Rzhevsky collection is one of the most famous productions from Ukraine during this period: Sergei Parajanov’s adaptation of Ukranian folklore in Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (Tini Zabutikh Predkiv). Audiences abroad, drawn to its fevered, kalaideoscopic style and auteurist vision, had far more exposure to this film than Soviet audiences. Yet most Westerners may not have realized that not only was the film in Ukrainian, but a Ukrainian so colloquial and regional that many Ukrainians could not understand it! Standard genres such as comedies and melodramas also appear from a variety of places. Gruziafilm (Georgia) is represented by a musical, Melodies of Verisky Square (Melodii Veriskogo Kvartala); Belarusfilm by some melodramas, The Street of the Young Son (Ulitsa Mladshogo Syna) and The Day One Turns Thirty (Den’ Kogda Ispolniaet Tpidtsat’); and Riga Studios (Latvia) by a melodrama, The Two (Dvoe).

A mix of traditional genre fair and more personal projects were in the output of minor studios, just as was the case in the Russian Soviet. With some exceptions, Gos’kino would dub projects into Russian from the original language from the Republic, if it was felt that the film was of sufficient merit to distribute across the USSR. One such exception found in the Rzhevsky collection is one of the most famous productions from Ukraine during this period: Sergei Parajanov’s adaptation of Ukranian folklore in Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (Tini Zabutikh Predkiv). Audiences abroad, drawn to its fevered, kalaideoscopic style and auteurist vision, had far more exposure to this film than Soviet audiences. Yet most Westerners may not have realized that not only was the film in Ukrainian, but a Ukrainian so colloquial and regional that many Ukrainians could not understand it! Standard genres such as comedies and melodramas also appear from a variety of places. Gruziafilm (Georgia) is represented by a musical, Melodies of Verisky Square (Melodii Veriskogo Kvartala); Belarusfilm by some melodramas, The Street of the Young Son (Ulitsa Mladshogo Syna) and The Day One Turns Thirty (Den’ Kogda Ispolniaet Tpidtsat’); and Riga Studios (Latvia) by a melodrama, The Two (Dvoe).

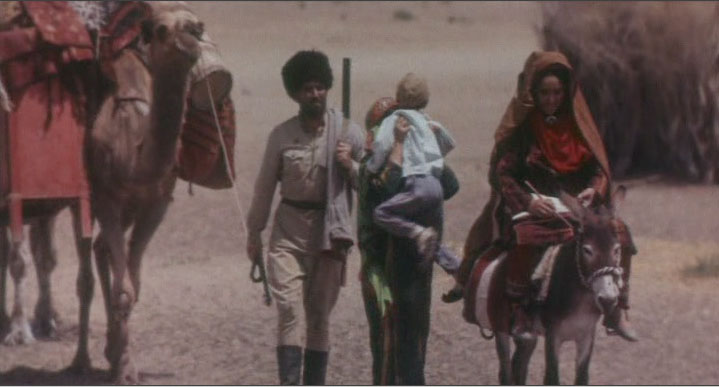

One particularly striking film in the Rzhevsky collection is, according to one scholar, “the film that put Turkmenistan on the map,” cinematically: The Daughter-In-Law (Nevestka). Though its earliest film dates from the 1920s, Turkmenistan was one of the last republics to have a significant film industry. More interested in evoking the rhythms of the countryside than telling a riveting story, The Daughter-In-Law follows the daily affairs of a young Turkmen woman who managed to only spend a few days with her new husband before he left for the front and perished there. In a structure that resembles Tarkovsky’s Ivan’s Childhood, her mundane chores are interspersed with intense visions of her husband (perhaps memories, perhaps fantasies) as she awaits an impossible reunion. In one memorable scene, a sorrow unexpressed in her restrained performance seems to be displaced onto the cries of a massive herd of goats at a seasonal shearing. If the film no doubt draws part of its appeal from the image of an exotic foreign culture, its portrayal is not romanticized—indeed, our central protagonist’s way of life seems to be a lonely and simple one. Despite its local concerns, the film would not be out of place at a film festival abroad.