The bulk of the Stuart Gordon Collection is comprised of production files, documents used to keep a record of every aspect of a film’s evolution from script to screen. Excitingly, the Gordon papers are nearly complete, allowing the fan or scholar to maneuver through almost every decision made on a given film. Included in this material are multiple screenplay drafts (in some cases as many as thirteen or fourteen), editorial comments and suggestions at the pre-production level, thousands of storyboards, budget breakdowns, memos from collaborators and studio executives, detailed shooting schedules and documentation of dailies, as well as plans for a film’s advertising, publicity, and Film Festival appearances. Although not production files per se, the collection also contains a great deal of critical and promotional material collected after a film’s release. Taken as a whole, the collection offers a fascinating glimpse at the creative process.

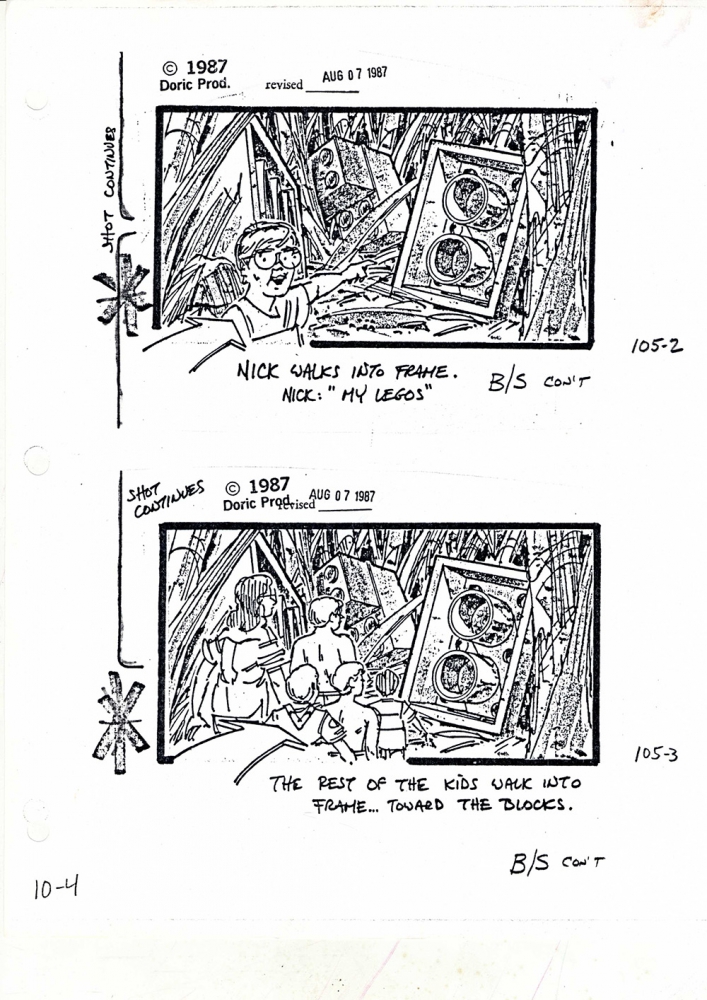

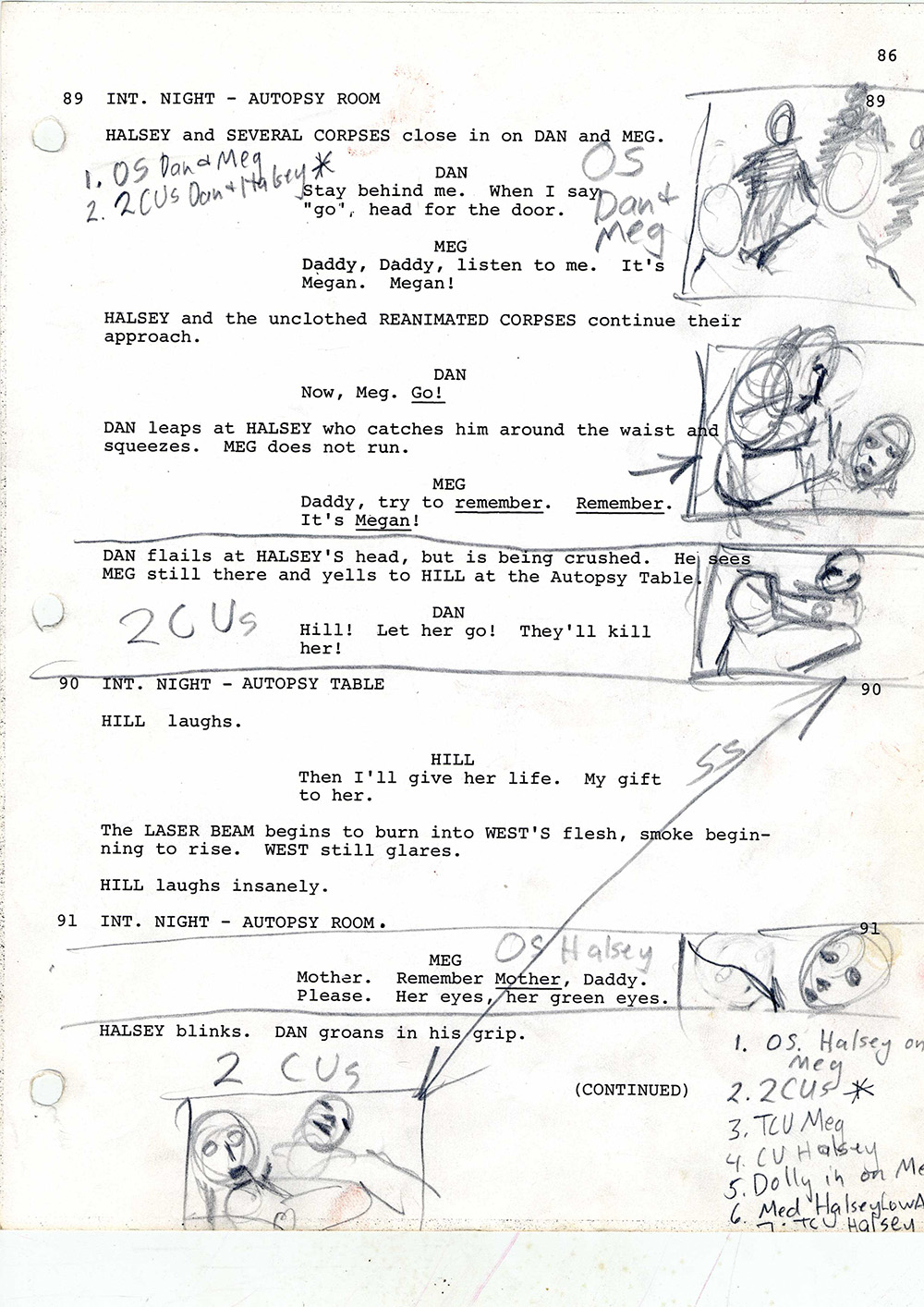

The collection also includes several of Gordon’s personal production binders. These thick volumes represent the actual material Gordon carried with him to the set as he made many of his best known films. In the case of Fortress, for instance, Gordon’s binder contains contact info for his entire cast and crew, the final script with pencil notation, a day-by-day shooting schedule with notes about necessary actors, props, or effects, elements related to production design, and the payroll schedule. A separate FX binder includes hundreds of storyboards related to the film’s elaborate visual effects and detailed breakdowns of all the optical effects shots. In an entirely different realm, one can also read correspondence between Gordon and Walt Disney executives on Honey, I Shrunk the Kids or personal letters between Gordon and Stephen King on Pet Semetary.

This material is revealing not only to fans of the director, but also to scholars who wish to trace the complicated relationships between a director and a studio or a director and his collaborators. It also provides the opportunity to compare levels of authorial control within the studio system and outside of it, as Gordon straddles the divide, sometimes working for studios, other times independent producers. A comparison between his early work for Empire Pictures such as Re-Animator and From Beyond with Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, made for Buena Vista/Walt Disney, could be particularly instructive. Regardless of the scholar’s specific interest, Gordon’s production files offer a nearly exhaustive look at all of the creative decisions that went into the making of his films.

This material is revealing not only to fans of the director, but also to scholars who wish to trace the complicated relationships between a director and a studio or a director and his collaborators. It also provides the opportunity to compare levels of authorial control within the studio system and outside of it, as Gordon straddles the divide, sometimes working for studios, other times independent producers. A comparison between his early work for Empire Pictures such as Re-Animator and From Beyond with Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, made for Buena Vista/Walt Disney, could be particularly instructive. Regardless of the scholar’s specific interest, Gordon’s production files offer a nearly exhaustive look at all of the creative decisions that went into the making of his films.