Playhouse 90 was, by general agreement, the last great live anthology drama on American network television. Fred Coe jumped from NBC to CBS in 1956 to work on this most lavish and expansive of live television anthology dramas, which required several producers—including the dynamic Martin Manulis—to produce each of its four seasons. As the name suggested, each episode ran 90 minutes, already a step beyond the typical 60- or 30-minute drama. Although Playhouse 90 featured the same wide range of subject matter as other anthologies, many episodes aspired to grand spectacle. Battlefields, sinking ships, and tropical jungles were all recreated for episodes of Playhouse 90, which was produced in both New York and Los Angeles studios. Playhouse 90 afforded Coe and his directors and crew a chance to experiment. The cinematography and mise-en-scène of many episodes became elaborate, even baroque.

Each episode of Playhouse 90 was an “event,” heavily publicized by CBS with television and newspaper advertising and elaborate-for-the-time press kits. Budgets inflated accordingly. While a 1952 episode of Philco-Goodyear cost, in Coe’s estimation, about $30,000, a 1959 episode of Playhouse 90 had a proposed budget of $175,000. The often-shocking cost of Playhouse 90 episodes sometimes became news itself.

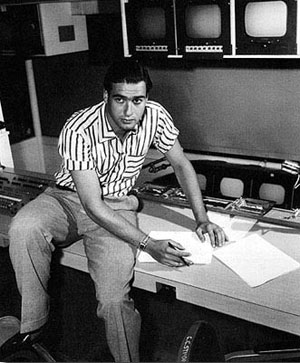

John Frankenheimer, a young director who had graduated quickly from less prestigious dramas, became something of a star for his intense, visually dynamic episodes. The flash and filigree of his later feature films, such as The Manchurian Candidate and Grand Prix, is already evident in his live television episodes. The WCFTR’s John Frankenheimer Papers include scripts from his episodes of Climax, Danger, and Playhouse 90, among other shows.

Although Playhouse 90 was highly successful, and many of its episodes went on to be adapted into feature films, it was also the end of the line for live anthology drama. An episode of Playhouse 90 might cost as much as—or more than—an episode of a filmed television series, but with much less potential for lucrative rebroadcast and syndication rights. As well, Playhouse 90‘s stories often called for special effects-heavy sequences that made great demands on the technology of live television. The show quietly began using the new technology of videotape, first for individual scenes but eventually for entire shows. Indeed, nearly half of the episodes were in fact broadcast “live-on-tape” rather than truly “live.” Without ever abandoning the conceit of “liveness,” Playhouse 90and other late-period anthology dramas made a good case for their own obsolescence. Coe’s papers document his growing anxiety as Playhouse 90 switched from weekly to biweekly to an occasional “special,” and eventually was taken off the air in 1961.

Producing Playhouse 90: “For Whom the Bell Tolls” – See here for an extended discussion of “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” a two-episode Playhouse 90 special broadcast in 1959.

Digital Docs

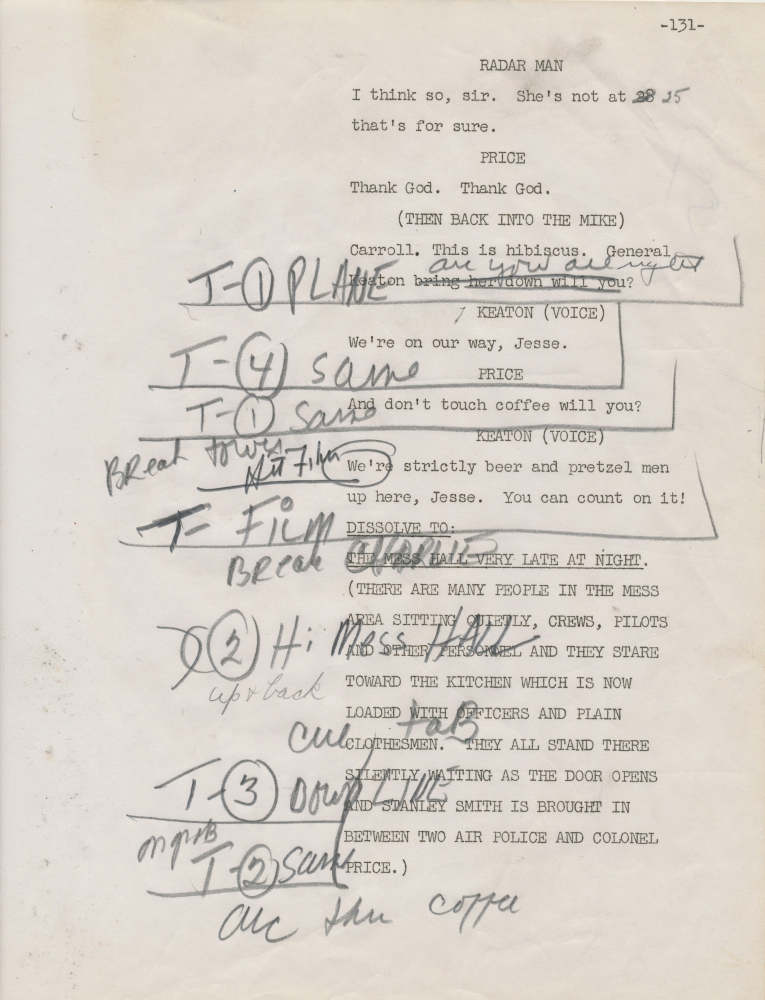

Page from Forbidden Area Script

Related Links

Encyclopedia of Television: Playhouse 90

Encyclopedia of Television: John Frankenheimer

Archive of American Television: John Frankenheimer

Further Reading:

Frankenheimer, John. John Frankenheimer: A Conversation with Charles Champlin. Burbank, Calif.: Riverwood Press, 1995.

Krampner, John. “The Minds Behind TV’s Most Fabled Anthology Take a Look Back.” Emmy 19:3 (June 1997), 35–37.

Levine, R. M. “Live from New York, It’s Playhouse 90—In the Beginning was Martin Manulis.” American Film 8:3 (Dec. 1981), 61–64, 72.