As the makeup of the organization’s membership broadened through its evolution from the HDC to H-ASP, so did its professional interests and political priorities. The organization’s battles over free speech—from campaigns for academic freedom to fights against radio and film censorship—illustrate one way in which changing affiliations helped shape its activist agenda.

HDC, HICCASP, and Beyond

In its early years as the HDC, the organization’s fights for free speech ran parallel to its larger pro-labor, pro-administration policy efforts. In 1944, for example, the HDC joined a campaign to defend University of Texas President Homer Rainey, fired by the Board of Regents for his insubordination during the board’s earlier attempts to curtail academic freedom by firing left-leaning professors, banning books, and violating the Fair Labor Standards Act. For the HDC, these cases were part of a much larger legislative agenda.

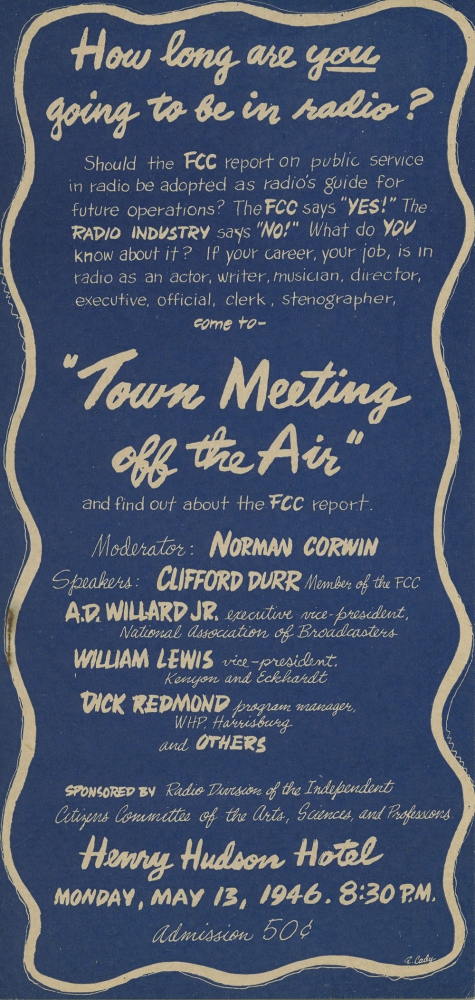

When the HDC affiliated with the Independent Citizens’ Committee of Arts Sciences and Professions in 1945, it zeroed in on liberal causes related to its members’ professional interests. Rather than broadly defending the general principles they located at the heart of Roosevelt’s recently terminated presidency, HICCASP responded to pressing censorship threats in its own backyard. Later, while reorganizing twice more—first as a chapter of the Progressive Citizens of America and then as part of the National Council of Arts, Sciences, and Professions—the organization kept its professional interests central in its battles over intellectual freedom. These later fights, often lead primarily by the academics and intellectuals who began to dominate ASP-PCA and H-ASP leadership, shifted the focus from freedom of the arts to academic and intellectual freedom more broadly.

Key Battles

Fighting the Un-American Activities Committees

Following the end of the Second World War and the dissolution of the US’s alliance with Russia, the US embarked on the infamous period of communist witch hunting known as the Red Scare. During this period, the Hollywood industry became a prime target for legislators who sought to control mass communication and ensure cinema’s distance from the taint of communist propaganda.

Entertainment and Academic Interests Meet

One of the organization’s early battles against these anti-communist forces at the state level intersected with the professional interests of both screen workers and academics within HICCASP. In the autumn of 1945, California’s Joint Fact-finding Committee on Un-American Activities(the Tenney Committee)subpoenaed UCLA provost Clarence Dykstra along with several other faculty members following UCLA students’ public protests against violence employed by Warner Brother’s studios to break up a protracted strike by set decorators. The committee based its investigation on the possibility that red-fascist sympathizing faculty encouraged the students to support union workers. The Science and Education Division of HICCASP, led by Linus Pauling with the support of Albert Einstein, Dr. Harlow Shapley, Vihjalmur Stefansson, Henry Pratt Fairchild, and other notable scientists, rallied behind Dysktra’s vociferous condemnation of the Tenney Committee’s actions. Together, members organized “The Threat to Academic Freedom in California,” a meeting publicly criticizing the UCLA investigations and seeking new strategies to fight increasing outside control over educators via loyalty checks and other means. Featured at the meeting were presentations by well-known educators and intellectuals including Roy Harris and Thomas Mann, whose speeches populate the WCFTR’s HDC collection of materials concerning the meeting’s organization and messaging strategy. Ultimately, the anti-communist hysteria of the California state hearings were but a prelude to the full-scale investigations of Hollywood personnel undertaken by the federal House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) two years later.

HUAC and the Hollywood Ten

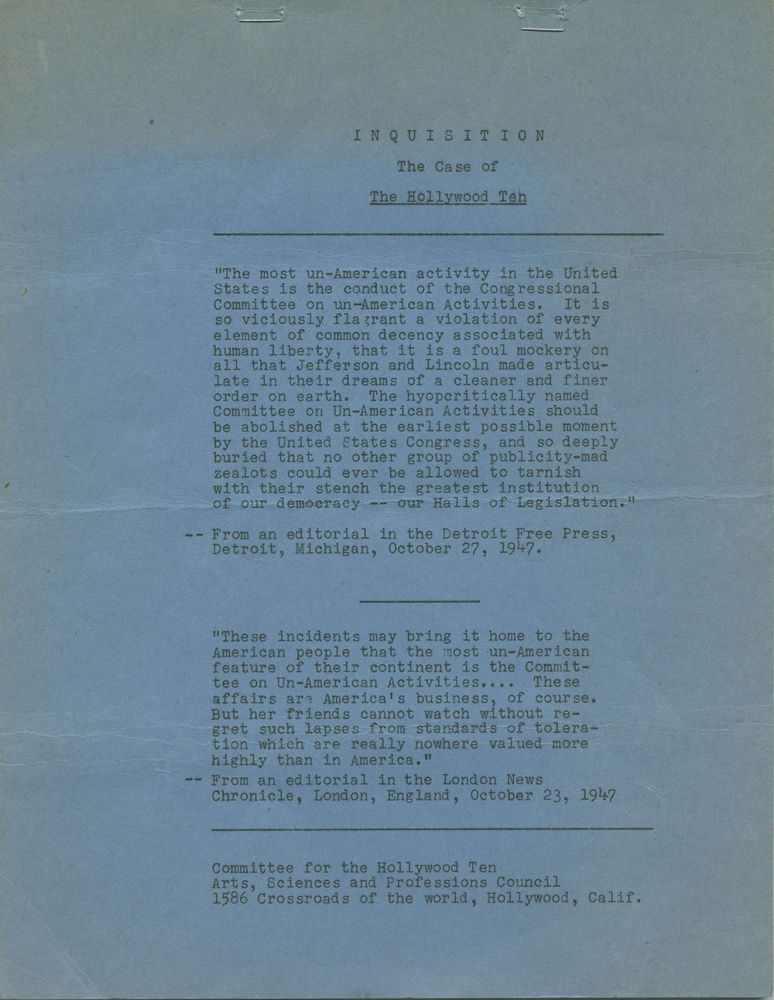

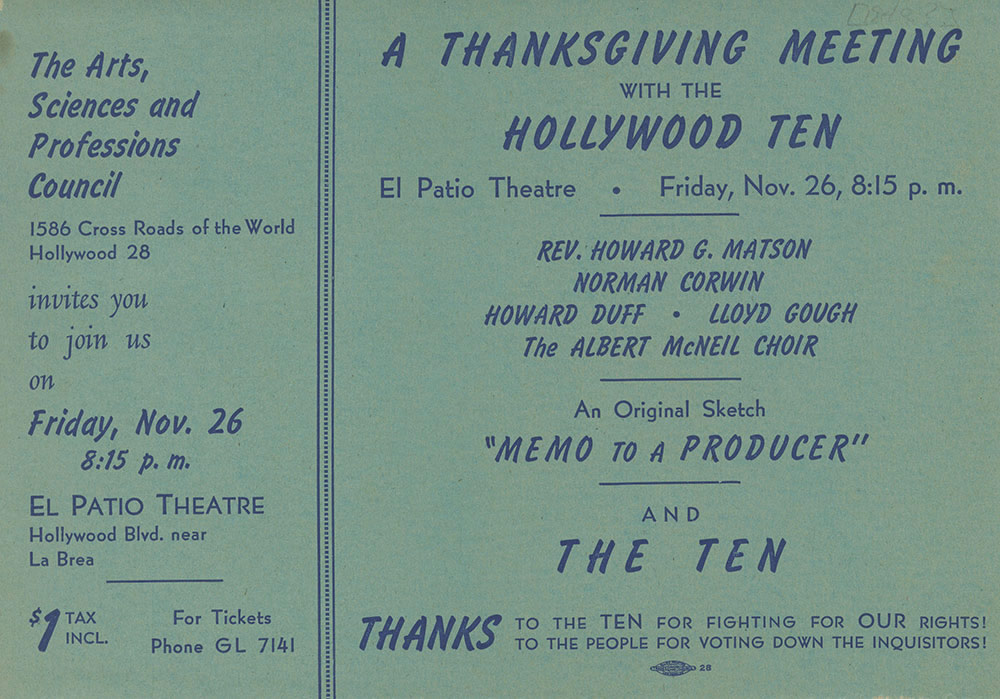

In 1947, as anti-Hollywood sentiment ran high in certain Washington circles, ASP-PCA—the organization resulting from HICCASP’s affiliation with the Progressive Citizens of America—sponsored a massive public meeting protesting HUAC and the increasing use of loyalty oaths. When a HUAC sub-committee famously subpoenaed nineteen writers, producers, and other screen workers for their possible involvement in the communist party, ASP-PCA responded quickly. In an attempt to fight what it saw as a move towards full-scale film censorship, the organization gathered and circulated materials damning the baseless accusations and intimidation tactics of the committee and linking HUAC members’ voting records on issues such as the poll tax and anti-discrimination policies to pro-Nazi, racist, anti-labor, and anti-progressive efforts. ASP-PCA also provided public and financial support to the Hollywood Ten, a subset of the nineteen originally subpoenaed who were held in contempt by the committee and subsequently blacklisted by the Hollywood industry for refusing to “name names.” Many members of ASP-PCA joined with other screen workers to form the Committee for the First Amendment, which actively produced and circulated protest materials, petitioned congress, and produced a national radio show for ABC called “Hollywood Fights Back.”

Continued Battles for Academic Freedom

ASP-PCA also worked on intellectual freedom issues beyond the confines of Hollywood. In 1947, it organized “Thought Control in the U.S.A.,” a small professional conference that protested the encroachment of control and censure into academia and everyday life and was published as a book. Also sold in affordable six-part installments, the conference proceedings offered ASP-PCA the ability to publicize and generate wider support for its efforts. ASP-PCA continued to battle for intellectual and artistic freedom into 1948 when the organization reformed as H-ASP, a chapter of the National Council of Arts, Sciences, and Professions (NCASP). As the federal HUAC committee turned toward scientists and other academics, H-ASP turned its focus once again to the university community. In 1948, H-ASP held its own “National Conference on Academic Freedom” during which it resolved to create a Bureau of Academic Freedom that would start chapters in major cities and on university campuses to fight loyalty orders, HUAC-style investigations, racist quota systems and provide legal aid where needed. Even when shifting towards fights for broader intellectual freedom rights, however, the organization did not abandon its interests in entertainment media. Answering a call sent by a coalition of prominent artists in various fields, H-ASP participated in the 1948 “All Arts Stop Censorship Conference,” which protested the use of blacklists and intimidation tactics as a means to dictate the content of movie screens.

The progression of all four organizations’ involvements in various freedom of thought campaigns reveals how the collective identity of a civic organization’s membership shapes its activist priorities. Although always concerned with censorship of the arts—especially film—the organization’s focus begins to widen in later years to meet the needs of its broader professional membership and combat the increasing attacks on scientists and university faculty. At the same time, this progression of battles over censorship and intellectual freedom also provides an overview of how the entertainment industry and the academy together shaped and were shaped by one of the more repressive moments in American history.

Digital Documents

We Stand Against Inquisitors Brief

Further Reading

Ceplair, Larry, and Steven Englund. The Inquisition in Hollywood: Politics in the Film Community, 1930-1960. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2003.

Hofstadter, Richard, and Walter P. Metzger. The Development of Academic Freedom in the United States. New York: Columbia University Press, 1955.

Krutnik, Frank, Steave Neal, Brian Neve, and Peter Stanfield, eds. “Un-American” Hollywood: Politics and Film in the Blacklist Era. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2007.

Langdon, Jennifer E., Caught in the Crossfire: Adrian Scott and the Politics of Americanism in 1940s Hollywood. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008.

Salemson, Harold J., ed. Thought control in the U.S.A.: The Collected Proceedings of the Conference on the Subject of Thought Control in the U.S. Hollywood A.S.P. Council, P.C.A., 1947.