The Fred Coe papers contain a wealth of material on the crafting of one of Playhouse 90‘s most famous episodes, “The Days of Wine and Roses.” These materials allow us to reconstruct the process of bringing the play’s difficult topic of alcoholism to the small screen.

In 1958, Coe wrote to William Dozier, a CBS executive, suggesting an episode about one man’s recovery from alcoholism to be created in collaboration with Alcoholics Anonymous. Coe noted that a writer named Henry Greenberg had already submitted a script about the history of A.A., which “bore no resemblance” to what Coe had in mind. (Greenberg would later threaten Coe and CBS with lawsuits.)

Coe solicited J.P. Miller, who had written “The Rabbit Trap,” among other teleplays, for Goodyear Television Playhouse, to craft a treatment. Miller’s first draft was called “One Step Home.” (Click to view the first page of the draft, taken from the WCFTR archives). It already featured the essential elements of what would become “The Days of Wine and Roses”: a couple, Phil and Mary Dorne, who fall into alcoholism. Phil joins Alcoholics Anonymous and cleans up, while Mary falls under the care of her father. Eventually, Mary too joins Alcoholics Anonymous. At the end, “Phil says a prayer of thankfulness that Mary has taken one step home.”

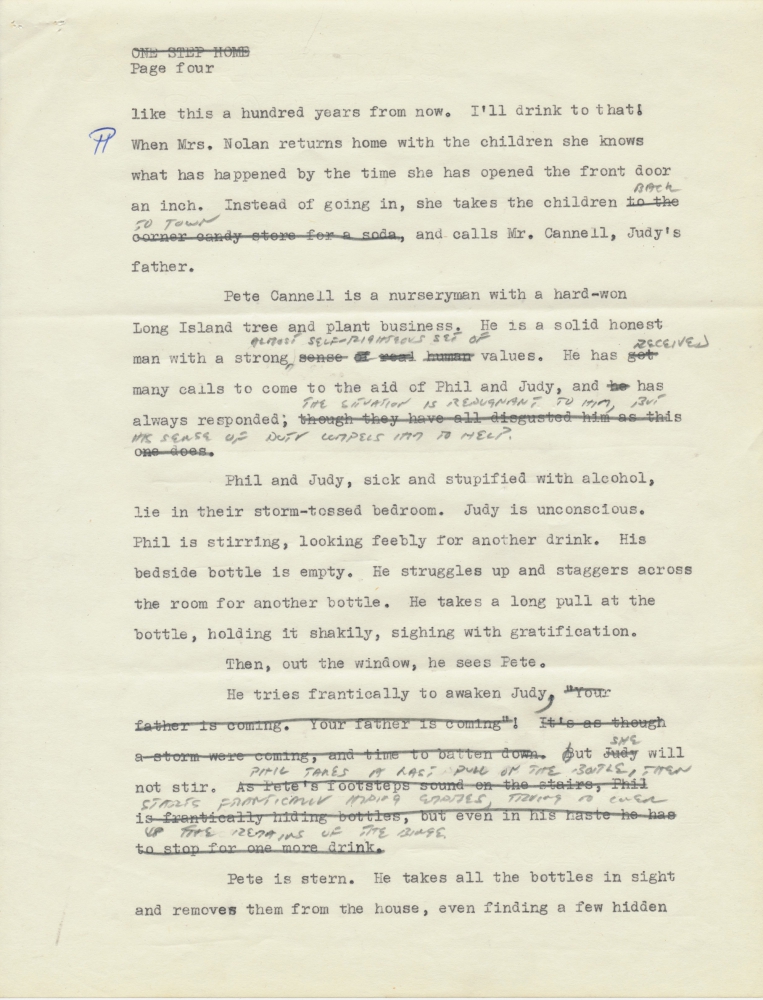

Miller’s next draft was retitled by Coe to the melodramatic “The Pit of Terror.” It provides more back story: how the couple (now named Phil and Judy) met, and how their drinking grew in the early years of their marriage—indeed, how it was an essential component of their relationship. Phil and Judy’s binges have grown longer and more sordid: Phil wrecks his father-in-law’s greenhouse searching for a bottle of whiskey he had hidden in a potted plant. The script again ends with both Phil and Judy in A.A., struggling heroically against their urges to drink. This draft shows how involved Coe was in editing scripts: it features his notes (in heavy pencil) on nearly every page.

The Coe papers contain several subsequent drafts, all titled “The Days of Wine and Roses.” The first, dated July 10, 1958, is 130 pages—a recipe for an episode far longer than the 90-minute show could accommodate. The couple, renamed Joe and Kirsten, follow an arc similar to that in the previous draft. But Miller adds a framing story to the first half of the teleplay, with Joe giving a speech in front of an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting. His speech provides the motivation for a series of flashbacks that recall the couple’s first encounter, their descent into alcoholism, and their first, failed attempts to recover without outside help. This draft, like the final version, is unusually explicit in portraying the impact of the couple’s drinking on their daughter and the humiliating lengths to which they will go to find a drink. However, the draft is also full of talky, didactic passages that explain for the viewer the disease theory of alcoholism (click for an example)—a theory that, while now commonly accepted, met considerable resistance in the 1950s from those who felt that beating alcoholism was simply a matter of individual willpower.

This draft resolves with Joe having seemingly conquered his addiction with the help of A.A. Kirsten is trying to do so on her own. The script leaves her fate unknown. It ends with Joe himself working as an A.A. counselor, helping others in their battle against the bottle. (Click to see the end of the script).

The version of “Days of Wine and Roses” that aired on CBS on October 2, 1958 was leaner, and arguably even bleaker, than this last draft. The speechifying was eliminated, as was the coda in which Joe has become an A.A. counselor. Instead, it ends, devastatingly, with Joe reciting the “Serenity Prayer” while looking longingly out of his apartment window at night, after Kirsten has just left him. The prayer’s line, “Grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change” takes on a sad resonance in light of Kirsten’s uncertain destiny.

Lead actors Cliff Robertson and Piper Laurie won great praise for their intense portrayals of the ravages of alcoholism, as did John Frankenheimer for his sensitive direction. The episode remains one of the best known of the era, and was adapted into a 1962 feature film, directed by Blake Edwards and starring Jack Lemmon and Lee Remick.